Portrait of the Artist as a Deaf Man, 1996

Framed photographic print, 70 x 60 cm

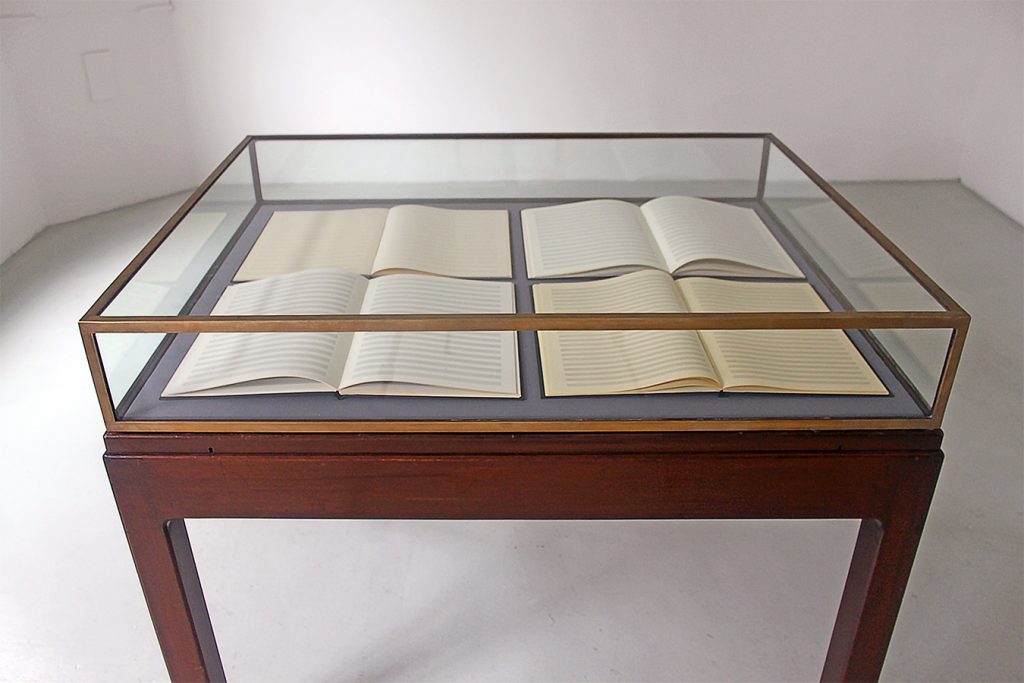

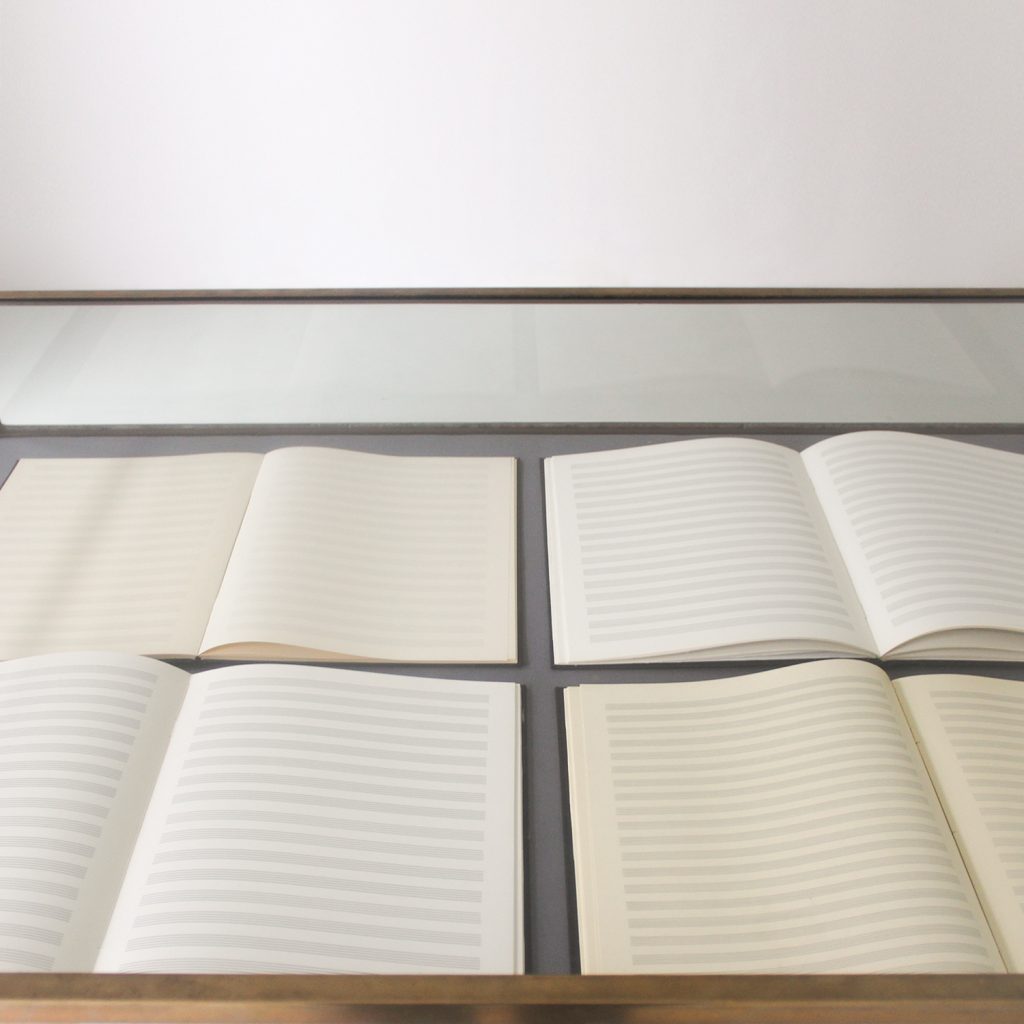

Selected works #2, #3, #6, #23, 1973

musical partitions, vitrine, h.99 cm

One of ltalo Calvino’s ‘Six Memos for the Next Millenium’ is concerned with the question of ‘lightness’. Quoting the De Rerum Natura of Lucretius, he muses on the idea that knowledge of the world tends to dissolve its solidity, leading to a perception of ail that is infinitely light and mobile. He talks, too (for these essays were conceived as lectures), of ‘the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness. Lucretius, he tells us, is a poet of the physical and the concrete, who nonetheless proposes that emptiness is as dense as solid matter. Just so, as lightness is inseparable from precision and determination. ‘One should be light like a bird, and not like a feather’, said the poet Paul Valéry.

If lightness has to do with the subtraction of weight, then this body of work by John Murphy is light. Several of these canvases carry merely the delineation of an ear; the others refer to the state of being that remains when all weight has been removed. ‘Selected Works’, blank music paper bound and displayed in vitrines, push that liminal state a step further into the unknown, for they exist in a permanent state of potentiality, somewhere between birth and death.

A point of entry into this weightless world may be through ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Deaf Man’, a recent work based on a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. To those who are in possession of all their senses, the condition of deafness, like that of blindness, can suggest both isolation and an acute awareness of an inner world. ln conjunction with ‘Selected Works’, are we to suppose that the artist, within himself, hears echoes of Baudelaire’s « La Musique », which was inspired by the work of the deaf composer, Beethoven? (‘l feel all the passions of a groaning ship vibrate within me, the fair wind andthe tempest’s rage cradle me on the fathomless deep- or else there is a fiat cairn, the giant mirror of my despair’). But perhaps he can hear nothing at all?

There is solitude in John Murphy’s work, as well as a little irony and a touch of the comic. (Calvino, again, remarks that ‘melancholy is sadness that has taken on lightness. Humour is comedy that has lost its bodily weight’). The space in these paintings is unidentifiable; it is neither close nor distant. So, too, is their colour, which is poised but unstable. Pink passes into blue; blue passes into pink.

Music and the metaphysical are seldom far apart. It is in and through music that many of us feel most intimately in the presence of meaning that cannot verbally be expressed. Murphy’s ‘Selected Works’ are either so full of meaning that they are inexpressible or, quite plainly, they have never existed. Like his paintings, the ‘Selected Works’ invoke the aesthetics of the sublime; they present the unpresentable to demonstrate that there is something conceivable which is not perceptible to the senses. The experience of the sublime, according to Kant, accords us simultaneous grief and pleasure, because it both opens and conceals. The sublime impedes the beautiful; it destabilizes good taste.

Francois Lyotard, who has written about a connection between the aesthetics of the sublime and postmodernism, suggests that it is the business of contemporary culture to invent allusions to the conceivable that cannot be presented – not to enjoy them but to impart a new sense of the unpresentable. Calvino makes a comparable point, more wonderfully. ‘Think what it would be like to have a work conceived from outside the self, he writes, ‘a work that would let us escape the limited perspective of the individual, not only to enter into selves like our own but to give speech to that which has no language, to the bird perching on the edge of the gutter, to the bee in spring and the tree in fall, to stone, to cement, to plastic… ‘. John Murphy conveys to us the activity of absence – its force and inner vitality.

John Hutchinson

Dublin, August 1996.

By titling her exhibition “Architectural Psychodramas,” Suchan Kinoshita effectively provides the salient keywords that lead to a possible mode of reception. Kinoshita invariably eschews fixed categories and definitions; she loves the changeable and the speculative. For her, architecture is built space, environmental space that influences us, but also some- thing that we shape. “Psychodramas,” experiences, memories and emotions stick to it, but without necessarily congealing; they remain changeable. This understanding of time and space, replete with the subject-object groupings and contexts of meaning that are constantly updated within it, also resonates recognizably in her background in music and performance art. The individual elements in the exhibition are not given one single role or meaning. Rather, it is about their “potential as objects,” as Eran Schaerf described it in the catalogue for Kinoshita’s exhibition at Museum Ludwig, Cologne (2010). As a result, there are countless connections to be discovered between the totality of the assembled elements, which coalesce and condense in a number of themes and ideas, no sooner to jump into another context once more. (…)

Suchan Kinoshita produce sounds with the help of birdcalls. She presents them via instruments, made with by hand and with incredible creativity, in a kind of aviary, thus also adhering to the principle of granting a physical presence to the acoustic components of the exhibition. These objects, too, are architectures in Kinoshita’s understanding, since they form a dwelling place for sound. And this brings us back to the never-ending topic of change- ability: when Kinoshita deploys birdcalls, it is by no means to imitate them. Instead, it is about the creation of something new. Just as it is with every memory, every object, every word.

Kristina Scepanski, introduction to the exhibition « Architektonische Psychodramen » Westfälischer Kunstverein, 2022.

“YOUR CLOCK WILL NEVER FADE LIKE A FLOWER (AH NON JE NE FAIS PLUS ÇA)”

oil, gloss, spray paint, wooden pieces, perspex, collage on canvas and wooden panel

60 × 103 cm

Pierre, Jacques et Jean endormis (thirty pieces of silver running away), 2024

Oil, spray paint, pigment and caulk on canvas / artist made frame; oil & caulk on canvas on wood, staples, 88 x 77 cm

Immer Realistischere Malerei / Je cherche quelqu’un, 2024

Oil, acrylic and acrylic mirrors on canvas in found frame, 64 x 52 cm