Jacques Charlier

Les employés du STP vous remettent leur bonjour, 1971

photographie NB, 25 x 35 cm

Jacques Charlier

Sculpture horizontale, 1970

plans et photographies couleurs, 200 x 75 cm (x2) et 140 x 75 cm (x2)

Jacques Charlier

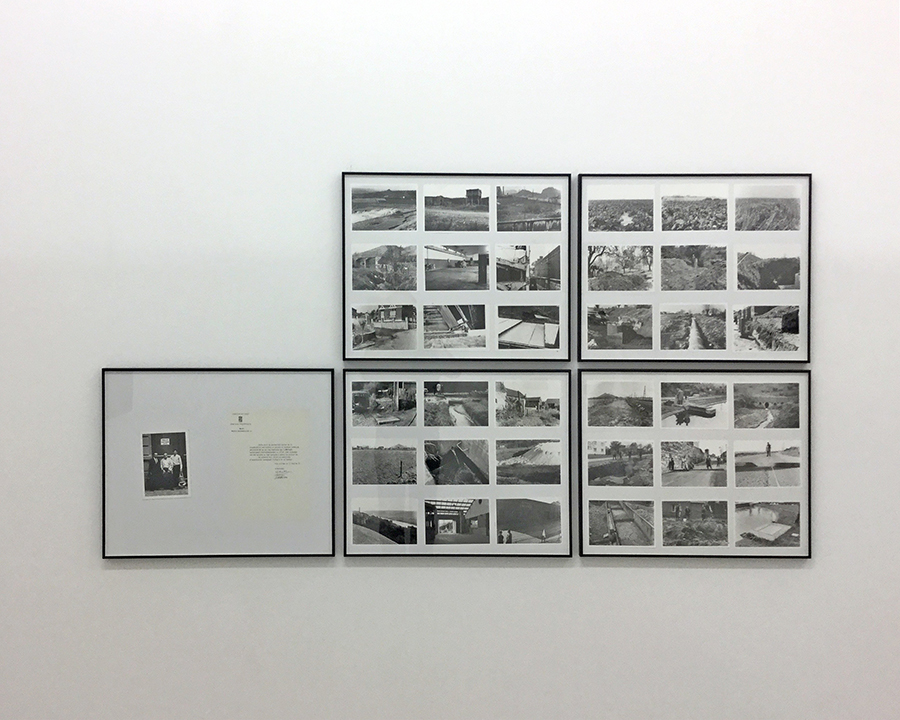

Paysages professionnels, 1970

photographies NB et texte imprimé, 70 clichés, 9 panneaux, (9) x 50 x 60 cm

Jacques Charlier

Papiers de protection de table, 1972

bandes de papier de protection utilisés pendant un an par les dessinateurs du STP, (4) x 30 x 40 cm

End of the sixties and beginning of the seventies, one of the fundamental practices of Jacques Charlier consists in pulling from their context a bunch of professional documents of the Provincial Technical Service (S.T.P.), where he is employed as an expeditionary drawer, and to distil them in the artistic field, to “present” them. Some of those documents said to be “essentially professional” are well known, this photographic documentation made by A. Bertrand, employed by the S.T.P., documents destined to the elaboration of road improvement projects, dewatering, waterways normalization, industrial zoning implantation, etc. But those are not the only documents Charlier extracts from their context. There are also the ones he names the “relational documents in relation with the professional universe”, documents bearing witness to, for example, a retirement, or a group trip to Antwerp offered by the solidarity fund of the Service.

We could store these with the “professional signatures”, a sequence of volumes regrouping the attendance sheets of the office staff (from 8h to 16h45) starting from February 68 and that Charlier presents in various artistic contexts, contexts in which the signature is precisely cultivated, although it’s the signature of the Artist, or even his famous pen dryers, these pieces of fabric of various sizes whose first function was to dry the graphos pens of the drawers of the Service. Jacques Charlier will hang these pen dryers in tight rows through various exhibitions, among others the Bruges’ triennial in 1974, in collaboration with Yves Gevaert or, a few months later, at the Oxford museum in collaboration with Nick Serota.

About these pen dryers, since then acquired by the museum of contemporary art in Gent, Gilbert Lascault, professor of art philosophy at la Sorbonne, wrote in 1983: “At about the same time, Jacques Charlier (who defines himself as a presenter of documents) presents rags in cultural centres: the pieces of fabric of various dimensions that were used to dry drawing pens. Those are canvas on which appear blotches. They can evoke non-figurative researches. They can remind the desire some artists have these days of collaborating with chance. They are presented without frames, not stretched, “pinned to the wall in a single point at the height of the drawing tables”: nothing keeps the specialists of art from seeing a thought (close to other artistic thoughts) in the frameless canvas… Jacques Charlier can’t forbid this way of reading them. However he always insists on the origin of these pieces of canvas: they are rags, used professionally, extracted from a very precise context, taken away from a technical service whose function is defined.

A conversation recorded between employees from the S.T.P. accompanies the exhibition of the rags. One of the employees asks: “Can we find this beautiful while knowing where it comes from?” It’s certain Jacques Charlier hopes the insistence on the origin of what he shows suppresses the seduction. Indicating the origin of the pictures and objects shown should, he thinks, “unexalt” them. But maybe he’s wrong on that score.

So Jacques Charlier extracts these rags from the S.T.P.; he does the same with their inevitable corollary, usual in this kind of professional environment: the blotter papers. Or instead, if we want to be more accurate as to the original function of these objects: “the protective papers of the drawing tables of the S.T.P.”, that he pulls away from their context in September 72. Charlier cuts them somewhat in A4 sizes and, to affirm their origin and their primary function, places on them a strip of text typed with a typewriter, a note identifying the object and the date of the excerpt. This identification is very important since, like the pen dryers, these papers are the backing of these same “non-figurative researches”, these blotches, strokes of pen, coffee stains, quickly written additions of measures, a few scribbled notes taken as reminders. All of this has the feel of tachism, of automatic writing, a lyrical abstraction contained, randomly, until exhaustion of the pattern, withdrawal of the figure, in short papers to be classified in a graphic department. Or this is all part of daily labours, hours and hours spent bent on the drawing table, the drawing that underlies road and piping maps. And in the fact of Charlier, a backward practice going against artistic appropriation, a query of the sociological neutrality of the object, a social perspective, the exact opposite of any illusionist’s trick. (JMB)

Jacques Charlier

Paysages professionnels, 1963-68

photographies NB et certificat, (4) x 50 x 60 cm

Those seventy black and white shots are documents born of a determined social-professional milieu embedded in an artistic context, accompanied by their certificate of origin by Jacques Charlier, expeditionary drawer at the Service Technique de la Province de Liège (S.T.P.; Provincial Technical Service of Liège) between 1957 and 1978. Jacques Charlier calls them “Paysages Professionnels”[1] (Professional Landscapes). Assembled nine by nine in eight panels, they are supported by a certificate written on the letterhead of the Provincial Administration. Charlier confirms that these photographies he pulls away from their context since 1964 have been part of the documentation of the project offices of the Provincial Technical Service and that they’ve been made by André Bertrand, chief data-processor of the Service. A photography of the building in which the Service and the transcript of an interview between Jacques Charlier and his colleagues, three pages of a tight typescript, complete the certificate. These photographs are absolutely not auratic and are in no way spectacular. They are only documents destined to the elaboration of projects of road improvement, waterways normalization or industrial zoning implantation, crude shots, a banal recording showing the reality of public works and other industrial wastelands. Even by their “presenter”’s words, they mean a complete expulsion of every traditional framing notion and even of a systematic “incomposition”[2]. In the beginning, this interview between Jacques, André, Joseph, Claude and the others who accompany these shots is published in November 1970 in MTL Magazine, at the moment when Charlier presents, for the first time in an exhibition, a large selection of these landscapes, invited to do so by Fernand Spillemaeckers, owner of the MTL gallery in Brussels. Jacques Charlier, already a fan of shock effects, titles it Les coins enchanteurs (The enchanting places). Enchantment, indeed, is absent. Already an ironic disenchantment transpires, characteristic of all the works of the artist from Liège, an activist who practices, as he says, “without exaltation”.

Jacques Charlier begins his collection of professional documents in 1964[3]. “I make friends with the office equipment operator and the photographer, whom I get to know since for whole days I made blueprints of roads, plans measuring six to seven meters long. I discover in the trash of the office equipment operating service some small pictures of a beet field. Those are perfectly banal pictures destined to illustrate the Service’s reports. What fascinates me is their brutal, unsightly aspect.”[4] Making a list of his activities at the S.T.P., Charlier will point out that André Bertrand’s photographs have been pulled away from their context as soon as July 64. Jacques Charlier considers this gesture to be the foundation of a research that will quickly become more precise, the one now called “of the S.T.P.”, to which we will associate his “Blocs” paintings, his works on the piping or of course the establishing of his Absolute Zone.

Self-educated, cannibalizing every information on art and its world, observer of the transatlantic flux — Pop Art is already well in place and soon the New York conceptual art will barge in Europe —, Charlier applied at the Provincial Technical Service in order to escape the factory. He becomes a drawer for public works projects while reading the works of Franz Kafka, by day working in an insurance company for work accidents in the kingdom of Bohemia and writer by night. Charlier, slightly romantic, identifies with this duality. He socializes with Marcel Broodthaers, with whom he made friends; both men share the same worries. “When Pop Art and New Realism barged home, he says, we were wondering how we could affirm our identity in relation to this American steamroller. How to do it also in relation with Pierre Restany and his French New Realists. Where could we find our place? More or less, I was considering Pop Art to be the result of considering publicity as a found object and to literally throw it in the artistic field after imbuing it with some aesthetic alterations. Warhol uses press pictures, Rosenquist publicity, Rauschenberg uses Schwitters’ Merzbau and set it in the American landscape. With Wahrol, all publicity is monopolized as a found object. Everything becomes found image, unvulgarized, crossed, culturalized”. In answer to American Pop Art, but also to the French New Realists, to the torn poster slices of Villeglé, the meal remains stuck by Spoerri, Arman’s buildups, this vast and systematic appropriation of the world, Jacques Charlier picks out of the trash of the office equipment department of the S.T.P. these few shots of beet fields, and decides to thus appropriate his own social and social-professional realities, to introduce them in the context of art, to sign them and to make a critical engine out of them. For Jaques Charlier, artwork has always been a Trojan horse.

Not even claiming to be part of Duchamp’s ready-made, Jacques Charlier simply declares himself “presenter” of those found documents whose origin he claims through protocol or certificates. He designates them, affirms their first function, confirms their attribution to their original signatories. In fact, by insisting on the ownership of these documents by his professional milieu, Charlier takes at the same time the opposite position of artistic appropriation while playing its game. He signs the work, or at least the presentation in an artistic context of those pictures and found objects, while clearly disclosing the manipulations of appropriation. The certificate of these Professional Landscapes attests it: it’s at the same time signed by Jacques Charlier and André Bertrand. Thus he sets his finger on what he will finally call the pompous art of the century, this principle of appropriation of any object, converted into an art form, an appropriation he qualifies of quasi-religious, that he considers to be a true transubstantiation, where any simple breath of air can become godly, resurrected, saved from the apocalypse and become, by the grace of this theology of art and the intervention of its preachers, a redemptive object destined to collectors. Charlier affirms it: “Telling that the object is only itself and nothing else is like still believing in miracles”[5].

The method will first be to “present” them to the actors of the world of art. Expeditionary drawer, Charlier goes for an expedition, his photos under the arm. He shows them to, among other people, Michaël Sonnabend. Admittedly, the artist looks for a place where he can exhibit them; notwithstanding, here are the Professional Landscapes already introduced in the artistic field, since shown to some of its actors. We can’t help but think of the driving principle of André Cadere’s wanderings: “the work is exhibited where it is seen”. They will finally hang, exhibited for the first time in 1970 at the MTL gallery in Brussels, then at the museum of Antwerp (1971) during Bruges’ second Triennial (1971), under invitation from Anka Ptazkowska at the Galerie 18, in Paris (1974), afterwards at the Vereniging voor het Museum voor Hedendaags Kunst in Gent and at the Museum Boymans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam (1981).

These Professional Landscapes are a single aspect of this documents collection. Charlier, very quickly, distinguishes between specifically professional documents and documents about friendship in the staff. Little by little, he pulls from their context prints, letters, communications, pen dryers, blotter papers and table papers, presence signature lists (entrance at 8h00, exit at 16h45), blueprints of his own road plans, souvenir documents about important events of professional life, like a goodbye party, Mr. Merciny’s retirement, or Mr. Herman and Mr. Tennet, a group trip to Antwerp organized by S.T.P.’s solidarity fund. It’s finally the entire S.T.P. that seems to become a found object. The word “seems” is the important one. Jacques Charlier writes it in a tract signed in 1973: “The experience comments backward this aesthetic-sociological current that, under the guise and the aura of the artistic signature, has simulated a vertigo of reality. As if from the things surrounding us, we could erase the meaning, the hierarchy, the origin of the objects”. I think again of Harald Szeemann who, speaking of his exhibition Grand Père, un aventurier comme vous et moi (Grand Pa, an adventurer like you and I), has written in 1974: “We don’t even discuss the thing any more, we discuss the frame that has, anyway, become perfectly boring: to fight for artistic reality is a fake fight, because we’re laughed at by the consensus beyond any controversy, or else it becomes a political fight, which is also a fake fight. Where then does the real rejection exist, the real enthusiasm, the bewitchment?”[6]

While he extract from the S.T.P.’s technical documents a sequence of printed pictures of piping public works, Jacques Charlier writes, in the protocol accompanying this reflection about his purpose: “Their enigmatic character, he writes, can not only rival some contemporary plastic researches, but surpass them through their tremendous expressive ability. But this is something no one will ever tell, or maybe too late. So it is today with art, turning to its profit under the guise of esoteric creation the reality of work, unbearable for the dominant cultural minority”[7] The Professional Landscapes wonders at these relationships with appropriation and estrangement. As a corollary, they also evoke anonymity. These landscape photographs are in fact poor and minimal; we could find similarities between number of them and Land Art or some minimalistic practices. Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Richard Long, Carl Andre are in fact not far; maybe, but here, the pictures have been taken by André Bertrand focused on his professional occupations and far from those of the artists. Their presentation is part of a completely conceptual frame, documentary inventory and certified protocol supporting it. Chameleon of the style and perfectly aware of the artistic practices of the time, Charlier therefore gets comfortable with the rules of art and its actuality in a time when grassroots, the streets and the banality of reality strongly imprint on the minds. Some have linked André Bertrand’s photographs and the great work developed then by Bernd and Hilla Becher, a windfall of sort for Charlier who challenges the title of “anonymous sculpture” given by the German photographs to their industrial typology. And Charlier makes a fuss about it: “Yes, those are industrial tools made by ground workers, conceived by engineers, used by workers, owned by bosses, every single one of them has a name”[8] All of this, for Jacques Charlier, is far from anonymous. It’s a testimony to the reality of work, it’s already signed. At the heart of this apparatus staged by the artist, Charlier naturally points at a social reality, a sociological reality. Undoubtedly the collection of landscapes also has a documentary value on the evolution of regional landscape, but that’s only a side effect of the purpose of the artist. Exactly as in the Photographies de Vernissages (1974-75) that, today, have acquired a documentary value regarding “who is who?” in the public of the exhibitions.

In fact, we could nearly paraphrase Harald Szemmann and subtitle the Professional Landscapes: “Jean Mossoux, Pierre Chaumont, André Bertrand, Jacques Laruelle, adventurers like you and I”. Their commentaries on the Enchanting places of the province of Liège are part of the works by themselves, starting with their own. Let’s revisit the situation. It would be like the prequel to another individual mythology, a collective mythology by proxy. After all, Jacques Charlier claimed to be the Director of the Absolute Zones the way others became Curator of the Eagles Department or flying Russian general on the Pan American Airlines and Company.

[1] The Smak in Gent, the M Museum in Leuven and the BPS22-collection of the Hainaut Province in Charleroi keep various series of Paysages Professionnels.[2] Jacques Charlier, Dans les règles de l’art, Lebeer-Hossmann, Brussels, 1983.[3]Dans Les règles de l’art, opus cit. Recently, during an exhibition on the Belgian landscapes, these Professional Landscapes have been part of the catalogue under the double date of 1964-1971. The date of 1971 is a mistake. It’s in 1970 that they were shown in an exhibition for the first time. The date of 1964 only represents the beginning of the adventure.[4]Jean-Michel Botquin, Zone Absolue, une exposition de Jacques Charlier in 1970, l’Usine à Stars edition, 2007[5] Dans les règles de l’Art, op.cit[6] Harald Szeemann, Ecrire les expositions, La Lettre Volée, Brussels, 1996[7] In the protocol certificate of Canalisations Souterraines, 1969.

[sociallinkz]