Jacques Charlier

Drapeau Total, 1967

Collection Ville de Liège

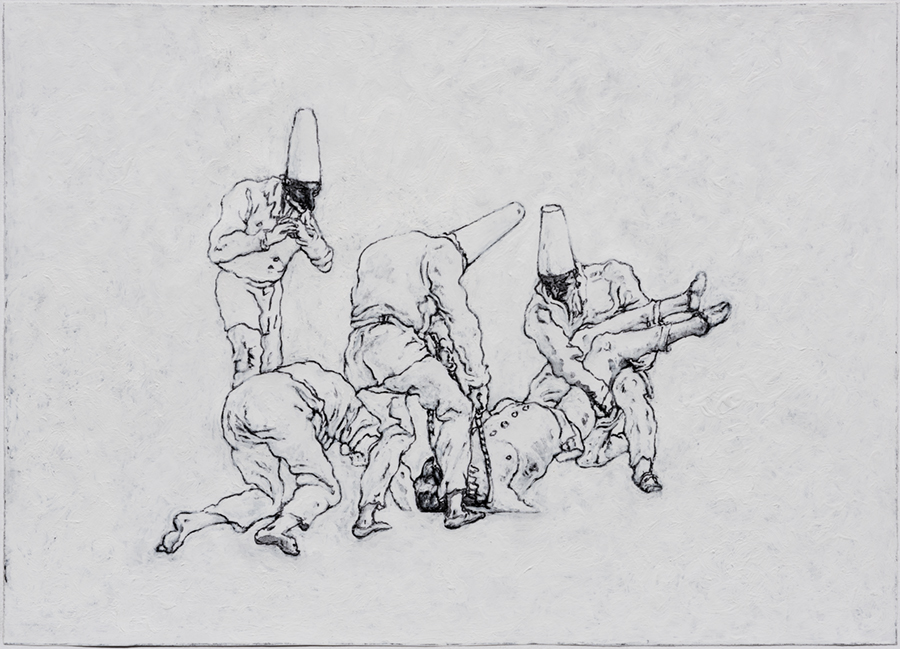

Jacques Charlier

Marche des Totalistes, 1967 (photographie Nicole Forsbach)

Impression sur toile, 100 x 120 cm

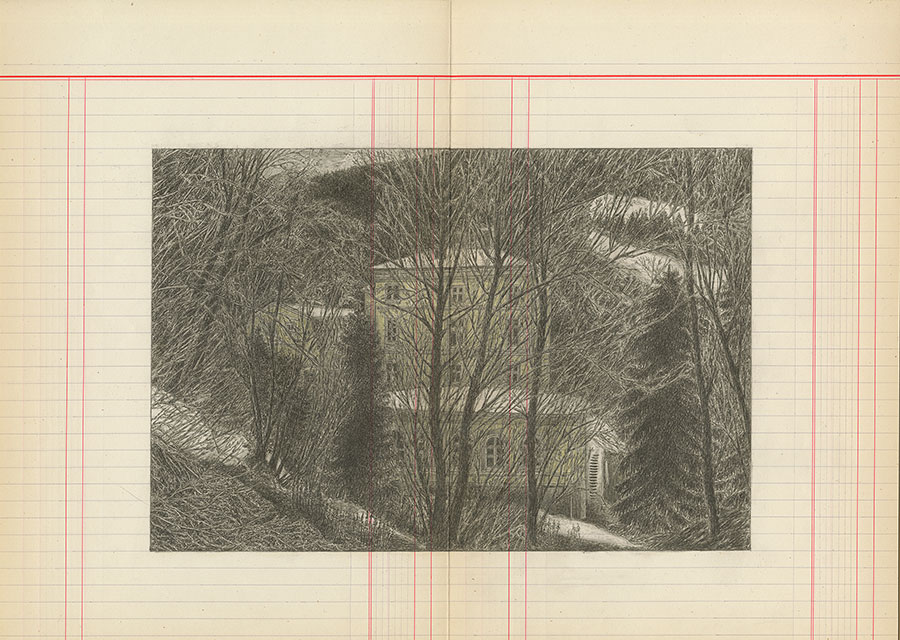

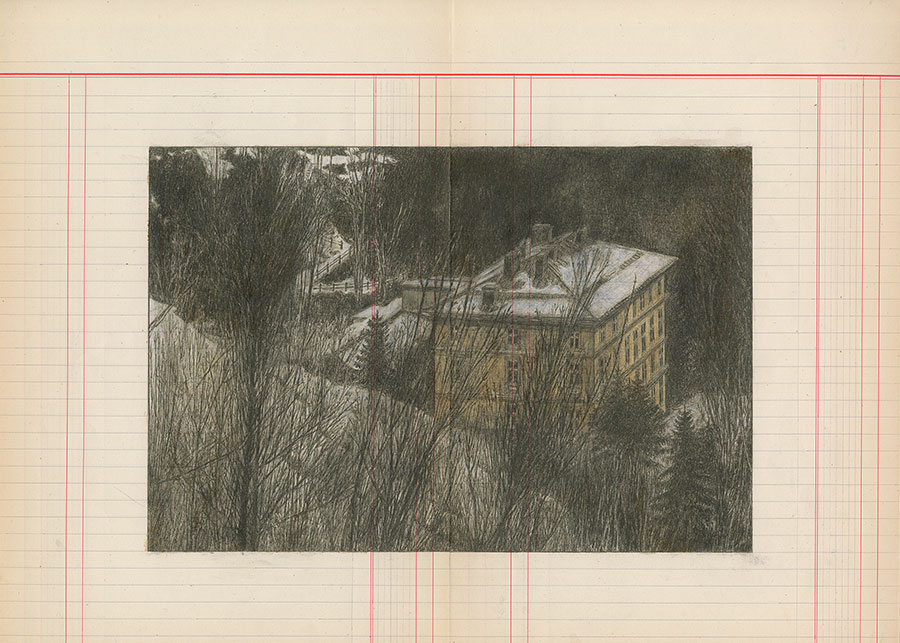

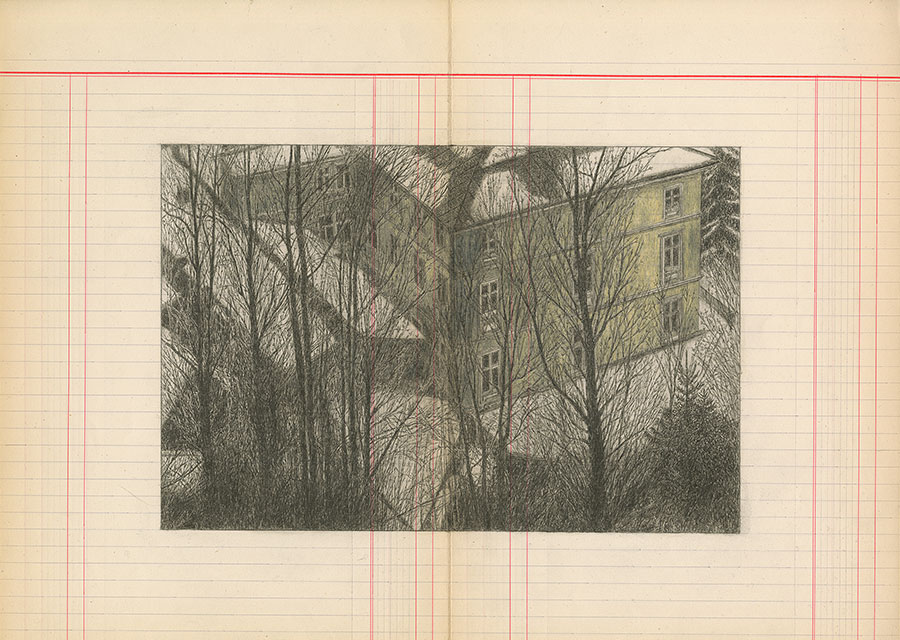

Jacques Charlier

Groupe Total’s Underground, 1965-1968

Ensemble de photographies NB, 52 x 72 cm

Au plus la transparence est objet de préoccupation,

Au plus le mystère s’est épaissi.

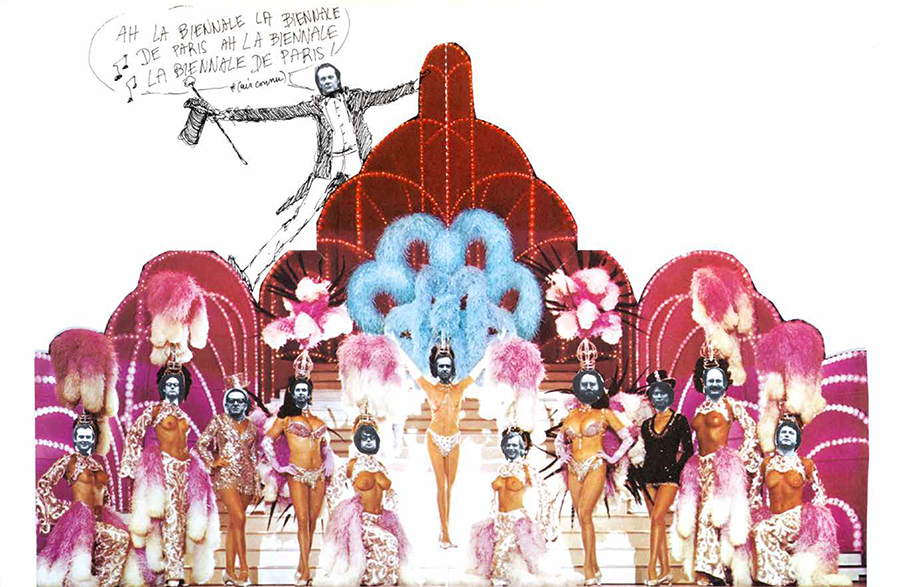

Il y a juste quarante ans, le 24 avril 1967, les Totalistes liégeois rejoignaient Bruxelles et la place De Brouckère pour la « marche belge anti-atomique ». Nicole Forsbach y prendra cette photographie devenue célèbre du Drapeau transparent totaliste, dessiné par Jacques Charlier, bannière flottant parmi les manifestants sous l’enseigne du concessionnaire Renault installé en l’ancien Hôtel Continental. Les Totalistes manifesteront en se collant un sparadrap sur la bouche, distribuant aux passants des tracts transparents. C’était là une action symbolique, une performance artistique, un happening au cœur d’un mouvement contestataire, « un dépaysement collectif ou une façon de démontrer une volonté de survie » pour reprendre les singulières prises de positions totalistes, c’était là aussi participer à la contestation, bref c’était de l’art total.

Jacques Charlier anime en effet à Liège de 1965 à 1968 le groupe « Total’s Undergound » et édite une revue intitulée « Total’s, l‘édition souterraine liégeoise ». La revue paraîtra irrégulièrement durant trois ans, comptera jusqu’à soixante abonnés.

« Total’s, écrit Jacques Charlier dans l’éditorial du n°1, livret stencilé et relié d’une couverture rouge représentant une cuvette de WC, une voie d’accès comme une autre au monde souterrain, Total’s n’est ni doctrine, ni philosophie, ni politique, ni anarchique, ni beatnik, ni provo, ni tout ce beau vocabulaire journalistique déformé par la consommation engendrant un racisme artificiel entre les générations et groupes sociaux. Total est le spectacle de la vie et de notre propre vie. Il n’espère pas, ne lutte pas pour une nouvelle « liberté » utopique où tout homme prendrait enfin conscience de lui-même. Il se contente de survivre dans des couloirs secrets sans vouloir persuader. Qu’on nous regarde vivre suffit. La révolution et l’évolution (si cela existe) n’est autre chose que notre manière de vivre « autre » qui nous permet de respirer, de créer. Non parce que nous le voulons et le désirons mais parce que nous ne pouvons « agir » autrement. »

Parmi les multiples activités, les styles et les médias divers qu’il pratique à l’époque, Charlier œuvre, en effet, dans la transparence, ou plutôt met la transparence en œuvre. Il crée même un pinceau transparent. « Si j’avais eu du blé, dit-il, j’aurais créé du mobilier transparent, une salle de séjour entière par exemple, comme une caricature du bonheur idéal. Que nous promettait-on d’autre qu’une vie en aquarium (transparent) dans lequel on pourrait se balader à poil ! La transparence était idéal de tout. La réalité en fut tout autre. Il nous faut bien admettre qu’au plus la transparence est devenue objet de préoccupation, au plus le mystère s’est épaissi» Tout dans la transparence donc, tous ces « désirs communs de bonheur, succès financiers, mariage, enfants, maison, santé, frigo, TV, chalet de campagne et danses sociales », lit-on encore dans l’édito de Total.

Les activités totalistes participeront de cette guerilla culturelle des années 60, cette large entreprise de démystification du conditionnement provoqué par la société de consommation. Mais avec un militantisme tout en nuance, car étonnante relativité des choses lorsqu’il s’agit de contester, Jacques Charlier précise dès 1965 : « Nos happenings sous des apparences provocantes ne sont que des essais de dépaysement collectif. En créant un événement où chacun est obligé de commettre un acte tabou, lequel l’oblige sans exaltation à quitter son environnement habituel. Ceci le fait pénétrer dans un monde où il croit ne pas avoir accès. Ce qui lui permet de se voir et de nous voir avec clarté hors de lui-même et si proche. »

At best, transparency is a concern,

At best, the mystery grew thicker.

Fourty years ago, on April 24th 1967, the Totalists from Liège got to Brussels Place De Brouckère for the “Belgian anti-atomic walk”. Nicole Forsbach will take this now famous picture of the Totalist transparent flag, drawn by Jacques Charlier, floating banner among the protestors under the sign of the Renault car dealer installed at the old Hôtel Continental. The Totalists will protest with a plaster on their mouth, distributing to the bystanders transparent tracts. This was a symbolic action, an artistic performance, a happening at the heart of a protest movement, “a collective change of scenery or a way to demonstrate a will to survive”, to use the unique positions taken by the Totalists, it was also a participation in the protestation, in short, it was local art.

Jacques Charlier indeed hosts in Liège from 1965 to 1968 the group “Total’s Underground” and publishes a journal whose title is Total’s, l’édition souterraine liégeoise (Total’s, Liège’s underground publication). The journal will be published irregularly for three years and will count up to sixty subscribers.

“Total’s, writes Jacques Charlier in the first editorial, stencilled booklet wearing a cover showing a toilet bowl, an access road like any other to the underground, Total’s is no doctrine, nor is it philosophy, nor politic, nor anarchic, nor beatnik, nor provo, nor all of this nice reporter vocabulary twisted by consumption causing an artificial racism between the generations and the social groups. Total is the spectacle of life and of our own life. It doesn’t hope, doesn’t fight for a new utopian “freedom” where every man would become conscious of himself. It simply survives in the secret hallways without attempting to convince. That our lives are accounted for is sufficient. Revolution and evolution (if it exists) is nothing more than our way of living “differently”, the thing that allows us to breathe, to create. Not because we want or desire it, but because we can’t “act” otherwise”.

Among the multiple activities, the styles and the various media he practices then, Charlier works, indeed, in transparency, or rather he puts transparency in his work. He even creates a transparent paintbrush. “Transparency was considered ideal for everything. Reality ended up being absolutely different. We have to admit that the more transparency became a concern, the thicker the mystery grew”. All in transparency then, all those “common desires of happiness, financial success, marriage, children, house, health, fridge, TV, lodge in the countryside, and social dances”, we furthermore read in Total’s editorial.

The Totalist activities will be part of this cultural guerilla of the sixties, this large business of demystifying the conditioning provoked by the consumer society. But with an activism made of many different shades, because surprisingly, when comes the time for disputes, Jacques Charlier outlines as soon as 1965: “Our happenings, under a provocative guise are only essays in collective change of scenery. By creating an event where everybody has to break a taboo, which compels him without exaltation to leave his usual environment. This makes him enter a world he doesn’t think he has access to. Which lets him see himself and us with clarity, out of himself and so close.”

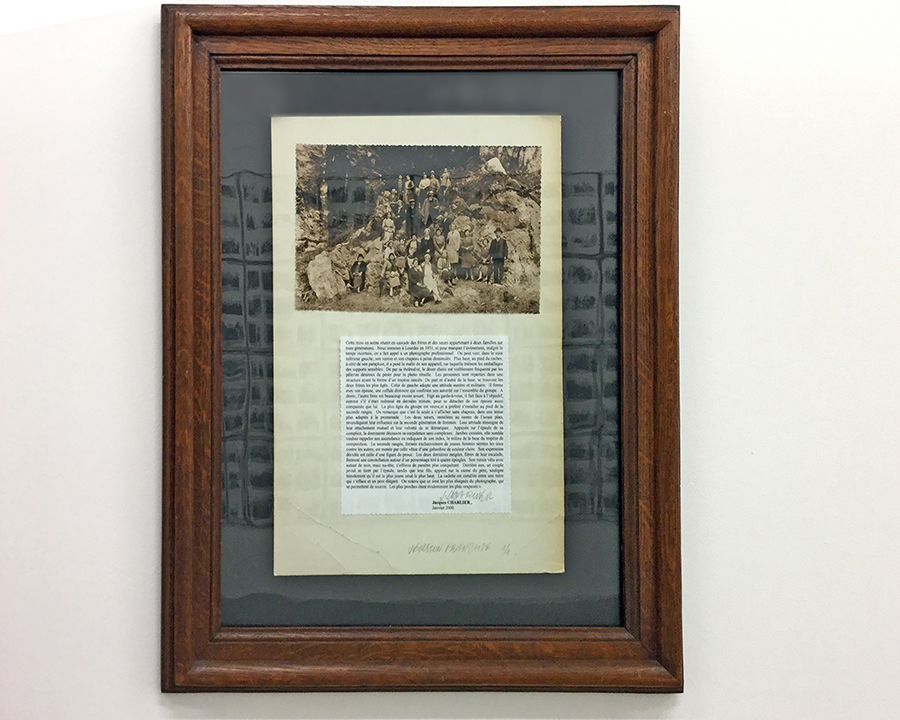

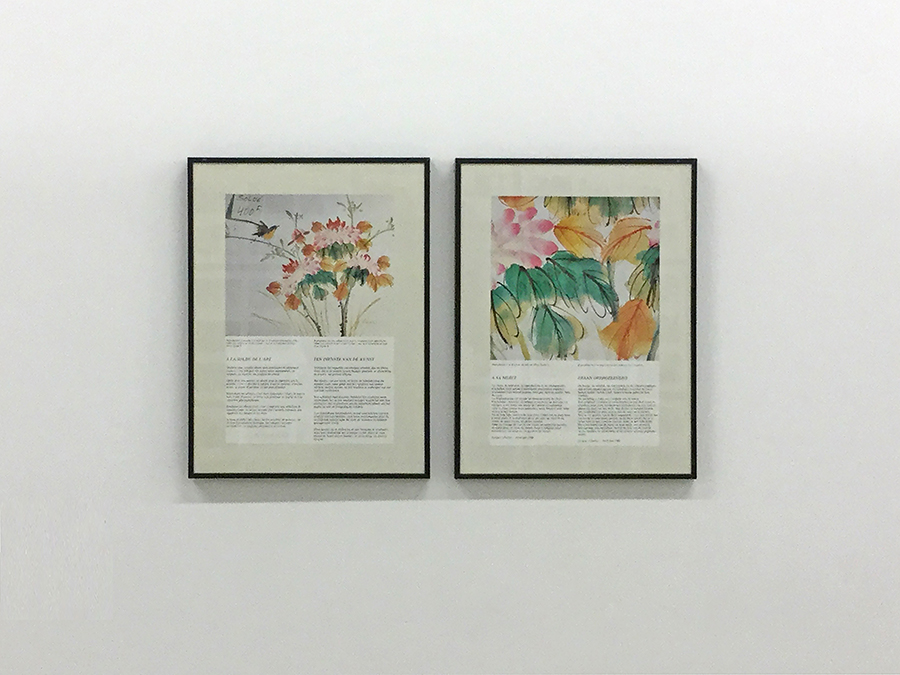

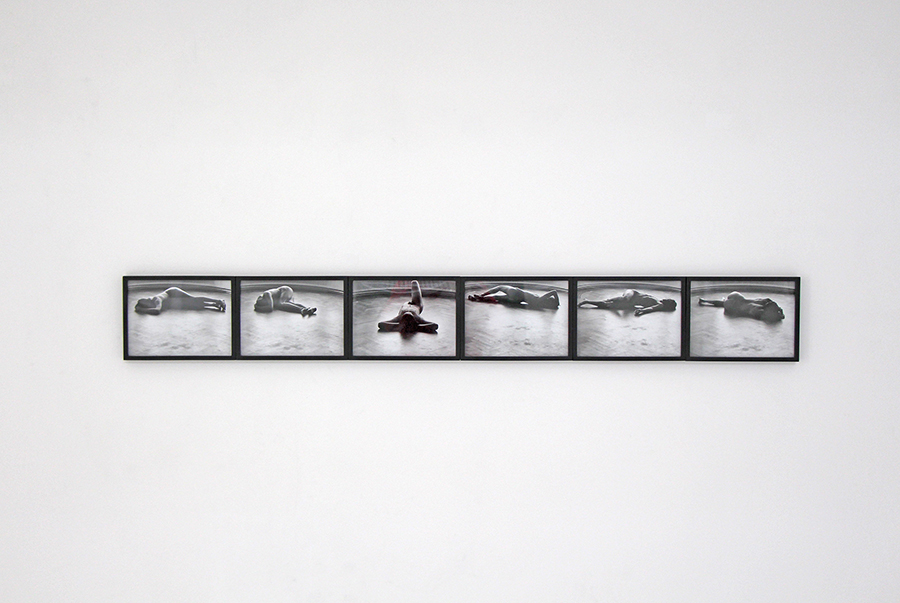

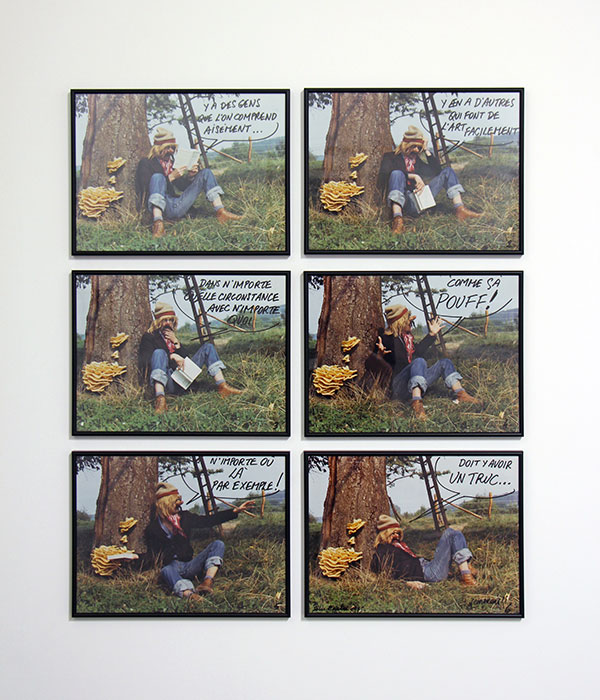

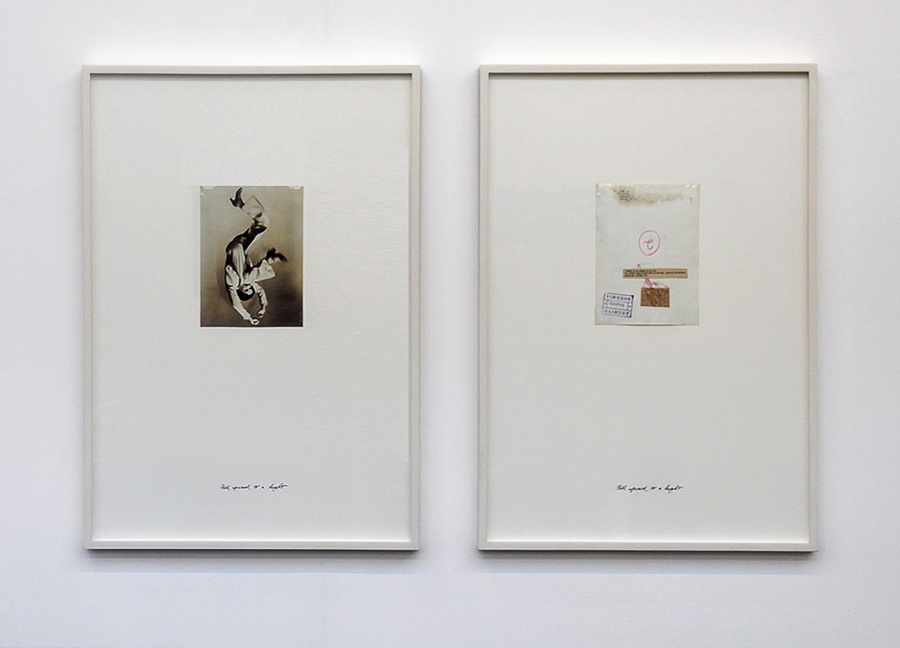

Jacques Charlier

« Photographies de Vernissages », 1974-1975

– Knokke, 4e foire d’art actuel 1974 (6 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Köln, Projekt 1974 (6 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruxelles, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Sol Lewitt, Darboven, Finlande, 1974 (6 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruxelles, réception chez Herman et Nicole Daled, 1974 (2 panneaux. Photos : Yves Gevaert)

– Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Sol Lewitt, (3 panneaux. Photos : Jacques Charlier)

– Gent, fête de Karel Geirlandt, 1974 (3 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruxelles, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Klapheck, 1974 (3 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruges, 3e triennale, 1974 (9 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruxelles, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Broodthaers, Cadéré, Ryman, 1974 (6 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Düsseldorf, IKI, 1974 (7 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Köln, Kunstmarkt, 1974 (7 panneaux. Photos : Nicole Forsbach)

– Bruxelles, Palais des Beaux-Arts, On Kawara – Jacques Charlier, 1975 (9 panneaux : Photos : Nicole Forsbach et Philippe De Gobert)

67 panneaux 60 x 50 cm, comprenant chacun 9 photographie NB 13 x 18 cm

In 1974, Jacques Charlier still practices professional photography within the Service Technique Provincial (Provincial Technical Service; S.T.P.) as an expeditionary drawer and turns the photographic lens towards the actors of the world of art itself. To various photographers who get involved with the project (Nicole Forsbach, Philippe de Gobert and Yves Gevaert), he asks to shoot pictures of a sequence of exhibition openings, for many reasons considered by the amateurs as being “essential”, and more precisely to shoot from afar, without exaltation we’d say, the public of those rendezvous. Charlier decides to take the public of art as his subject. The point is not to take pictures of the works. Neither does the artist enlists for a worldly photo report. He explains his motivations: “In 1975, the art I was frequenting was increasingly closing on itself. The same little world it interested was moving along with the exhibitions. Since there was nearly nothing on the walls, it was becoming a ritual in its purest form. People had been criticizing me for exhibiting pictures of parties and trips happening in the context of the S.T.P.. I was absolutely not proposing these documents by exoticism, but I was aggressively criticized as exhibiting alienation… My motivation was instead to get into open conflict with poetic photographic scouting and socio reports. I was still wondering about the problem of the sociological index of the objects and its impact, the involvement of the one who shows, of those it shows, of those to which it’s shown. In the case of the S.T.P., everything was really intractable, nothing was legal, defensible, legitimate. Everything was short-circuiting. This aspect of impossibility was my fascination… Nothing was neutral. This complexity was making the product absolutely indefensible for the market. Some kind of an inextricable no man’s land. To answer some arguments, I decided to turn the artistic context on itself.

So for a year, Charlier multiplied the panes, nine black and white pictures per nine, composing them with a perpetual care to notice the sociological index. He went to the high masses, Bruges’ third Triennial, the Köln Projekt, also the fairs, the one in Knokke, the Kunstmarkt in Köln, very avant-garde, IKI in Düsseldorf which was way more like an art bazaar. He joined the Stedelijk museum in Amsterdam for a Sol LeWitt exhibition, went a few times at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where Marcel Broodthaers, Hanne Darboven and Klapheck were exhibiting. He even entered private parties, those given in honour of the tireless Karl Geirlandt at the Gent museum, an evening between friends at Nicole and Herman Daled’s place (two collectors from Brussels). He proposes these/his photographs. “On Kawara’s activity is completely centred on his life, he says… The time at which he awakes… The people he meets… Today’s date… In short, a program tight enough it’s going to give you a headache (laughs), a bargain for the telegraph management (laughs)… the conception of the frames of my exhibition photographs was inspired by Bertrand’s photo reports, S.T.P.’s photograph… The average plane and taking the overview of the situation… the most complete deployment of the back of the tableau, of what’s in front of it… Exactly the opposite of the works centred on the artist and also the opposite of the usual exhibition picture, in which the moral perspective inherent to the exhibition is restored… the artist, the organizers, the close-up shots of high-profile personalities, the public behind… the extras… The exhibition of the pictures of the whole array of these pictures happened at the end of the exhibition and matched the publishing of the catalogue collecting the photographs of the people busily attempting to find their faces on the pictures… the experience could have continued, becoming a mise en abyme”.

Jacques Charlier had already played with this mirror effect, confronting the public of the exhibition to itself, although in a different way: with the group Total, during an exhibition of the APIAW in Liège, around the end of the sixties, he introduces in the exhibition room a great mirror on which is written “Tableau Total” (Total Tableau). The viewers faced with their reflection become the object of the exhibition. Is the same mirror effect effective in the case of openings photographs? “No, a mirror doesn’t capture time, answers Charlier… The ritual of photography is the same as nostalgia… Memory… Over time, the public’s interest in those photographs grows, everybody can find themselves in them… We progressively count the missing… a “work in progress”, as the ones who would like to say something about it say…”. It’s one of the points of interest of this work. “The document offers the privilege of retrospectively lending meaning to the things – it’s also true in the world of art, Shawn McBride writes about the pictures of Benjamin Katz, who developed for half a century through his photographs a panoptic vision of the world of art and of its protagonists. And many artists didn’t have the chance right then to appreciate its full scope. We can feel how these things grow with cruel speed when we observe their progress. But do events really fit this way together? The real experience certainly wouldn’t allow us to see the big picture like we perceive it with hindsight. This experience happened in the flux of the moment – and not necessarily in the remaining material that is the artwork. Often, photography transmits more than its essence”. De facto, with hindsight, Jacques Charlier’s openings photographs have become an exceptional fonds over a very short period of art history. Over the course of the pictures, we actually recognize an impressive number of “personalities”, actors of this artistic corporation. Artists, museum directors, collectors, gallery owners, critics, in short this little world, this family considered to be nearly incestuous and infatuated by some who have a critical eye, while others will evoke it with nostalgic attachment, happy to have been part of it or regretting that they didn’t get to rub with Konrad Fischer, James Lee Byars, Marcel Broodthaers, Anton Herbert, Daniel Buren, Benjamin Buchloh, Isi Fiszman, Giancarlo Politi, Catherine Millet, John Gibson, Dan Graham, Ilona Sonnabend and so many others. The analysis of these photographs is obviously edifying on many aspects of the world of art and on its rituals, its perfectly codified exhibitions, this unique ceremonial where the public varnishes itself since we don’t varnish the paintings in public any more. The ritual consists in receiving, since this is a reception, but what do we receive in fact? Do we receive each other? Do we receive the works? Most likely, this is the dwelling place of the topicality of this work by Charlier. It radically questions the art object in itself; it’s certainly its basic necessity. Through the last exhibition pictures, those from 1975, those on which we see the public watching the openings photographs, we wonder of course about those questioning looks. Is he questioning the work? Is he questioning himself? Is he questioning his own presence? In addition, the work establishes what we now understand as a sociological tour taken by creation over time, it questions the heart of this artistic field, it is a way of thinking its reception, its artifices, its reality. It continues even now to send the viewer back to himself.

Didn’t Édouard Manet say “The Exhibition Room really is a wrestling ground. It’s here that we compete”? This is also topical.

[sociallinkz]