John Murphy

Fall upward, to a height. 2015

Stuffed Black Rooster, rope, pen and ink on publication, vitrine, variable dimensions.John Murphy

Opened in a Cut of Flesh. 2015

Framed postcard, pen and ink on board. 84 x 62 cm, pen and ink on publication, vitrine, variable dimensions.

John Murphy

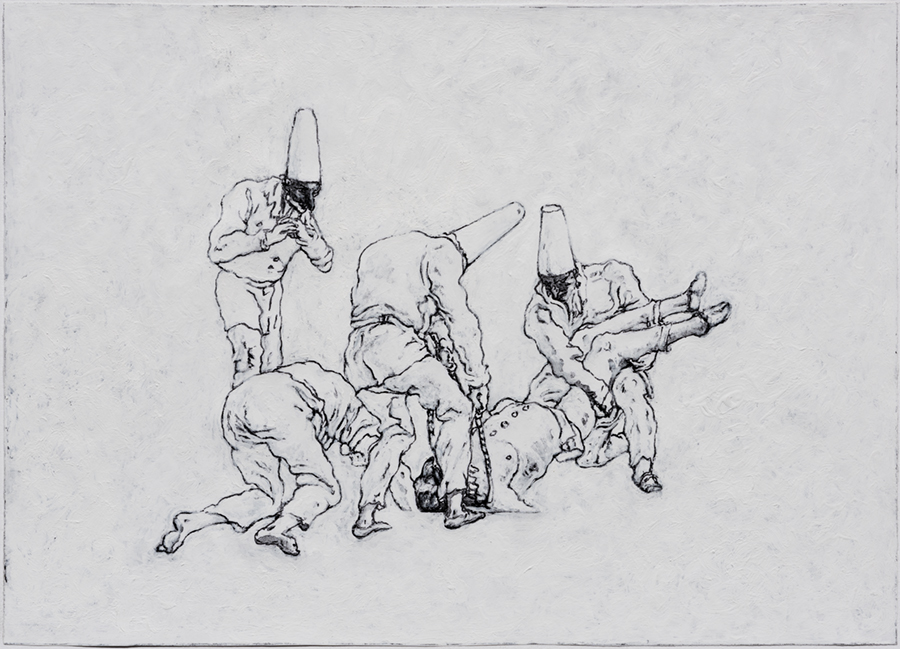

Cadere: Waste and Cadavers All. 2015

photocopy, gouache, pen and ink on paper. 46 x 54 cm

John Murphy

In the Midst of Falling: The Cry… 2016

145.4 x 241.8 cm C-print (Unique), Satin Float Glass and Gesso Wood Frame.

(…)The idea for Show your Wound comes from a paradoxical work by Joseph Beuys, an installation or environment called Zeige deine Wunde (Show your Wound), which is discussed in depth in this publication’s essay by Antje von Graevenitz. Zeige deine Wunde raises questions of how we take care of nature, ourselves and society, and it seems to emphasise notions like responsibility and awareness.

This work was first made in an underground pedestrian passage in Munich in 1976, and in 1980 became part of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus collection. In the muséum Beuys built a room for the objects: two morgue tables on wheels (‘beds’ in Beuys’s words), two blackboards with a call-up (‘Zeige deine Wunde’) written in chalk, two glass cases on the wall with papers from a Turin-based left-wing political organisation (Lotta Continua), and two pairs of garden tools. All the objects suggest ways of nurturing human life, attending to nature and culture, but they have come to a stand still. Today we can read that ‘Beuys created the environment for an underground passage. Its aura of melancholy and mourning arises from its charged subject matter: death, decay and a sense of trauma that Beuys referred to as “the wound”.’ What is absent in the work, I would argue, takes on presence in our imagination: man and nature, an energised world and society of living beings. Today this work reminds me of Malevich’s Black Square, especially of the photo of the Polish-Russian artist on his death bed, his painting on the wall behind him, radiating above his saintly head.

Today we see more clearly Beuys’s concern with nature and with man as part of nature; with the social body and with Western society’s development. The artist’s empathy for the individual and belief in the human potential for inner growth continues to inspire.

However, we also live in different times: the recent rise of scientific notions such as the Anthropocene and the posthuman condition indicates a huge paradigm shift and suggests that we have to think and act differently now, to survive as mere humans in a world whose

system of natural elements and tissue of social relations is impaired by our wrongdoings. This awareness is reflected in the art of artists such as Kader Attia, Pierre Huyghe and Sióbhan Hapaska, who seem to have been touched by Beuys. It is my consideration of their work

that has led me to think that at present Beuys has new relevance for artists.

Beuys’s work is no longer eclipsed by his words, by the dominant presence of what he said in public, and this has created space for artists to connect with this significant artist once more. Here we should realise that in general processes of transmission are miraculous. As a rule we could perhaps say that what informs or shapes the work of artists who process the achievements of a preceding generation are imponderabilia : an élective affinity (Goethe’s Wahlverwandtschaft), a constructive resistance, and a ‘creative misunderstanding’ in literary critic Harold Bloom’s words.

There is a religious ring to the title of this exhibition. The words Show your Wound resonate both with Christian and pagan tones and recall a twelfth-century story in which the knight Parsifal is on a spiritual quest to find the Holy Grail and heal the wounded king Amfortas (artistic and musical interprétations of the story are offered by Wagner and Beuys). This connotation is quite intentional: etymologically ‘religion’ can be derived from the words ligare (connect) and religare (reconnect). Here the idea is perhaps that art has a larger place in society and that the artist Works in the service of mankind for a common goal. A visit to the Moyland Castle, which houses the Beuys collection of the brothers Van der Grinten, will convince both art connoisseur or laic that Beuys saw his art in the service of a larger total. This brings me back to Joseph Beuys’s Zeige deine Wunde. I propose to draw a web of lines from this environment to the work of the seven artists in Show your Wound.

(…) John Murphy, who is of Federle’s generation, has asimilar respect for art from the recent past. His art resembles a pantheon of signs that transmit poetic experience. He engages with existing works from a modernist body of literature, painting and film, and particularly with a number of ‘authors’ who (re) invented Symbolism (Mallarmé, Magritte, Resnais). His work often comes in the form of delicate objects or images that sit or hang lightly in a space, like a spider’s web or celestial notations. In fact the physical space between the elements in his work is essential and signifies the mental space that opens up when a visitor tracks the (symbolical) lines that connect the elements, and when words, images and associations reveal themselves. Our exhibition features a body of works inspired by the notion of the fall, especially the fall from grace recounted in Genesis, when Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden, as famously depicted by the Italian painter Masaccio in a fierce and moving fresco. Masaccio’s painting returns in Murphy’s epic, newly made photograph In The Midst of Falling. The Cry (2015), which derives from a charged image in Joseph Losey’s film Eve (1962), where a woman is transfixed in a hallway before a reproduction of the painting. Murphy is like a dancer aiming for a light gesture, because for him it is the most powerful conduit of experience. His titles, resourceful and full of sillent threat, create a world in itself. (…)

Mark Kremer, in Many Moons and a Single Star (I’m Lost in One Breath). Meditations on the exhibition Show your Wound

[sociallinkz]