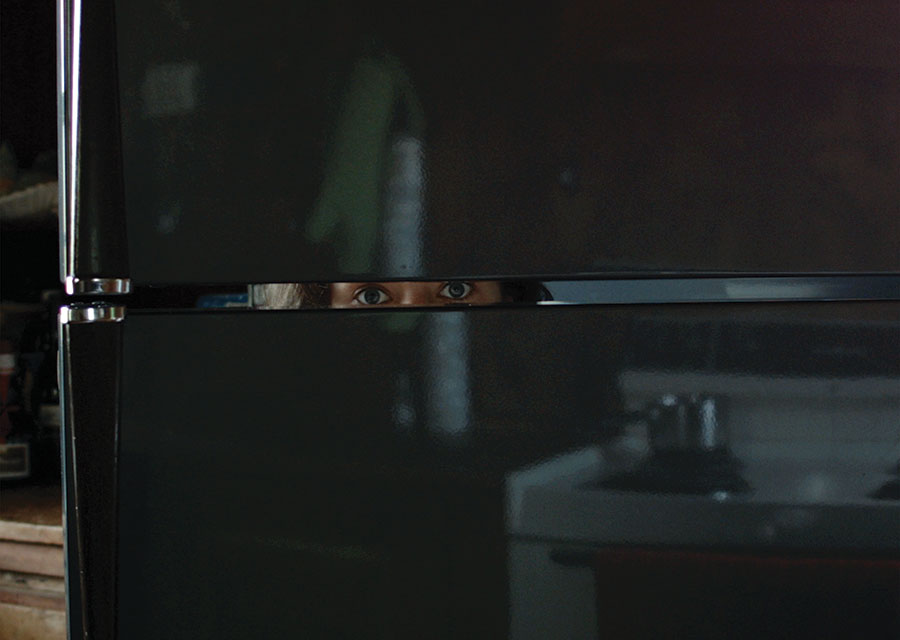

Invited to speak at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 1996, artist Gary Hill began his lecture by referring to his very arrival on the school campus, an old farmhouse situated in the heart of a vast rural area of 350 acres in Maine. ‘Well, hi, ah, he said, I don’t really know what I’m gonna do here.’ Hill then talks about his arrival the day before, at around 11 pm, he talks about Seattle, where he lives and works, about Philadelphia, where in that same year, 1996, he exhibits Withershins at the Contemporary Art Institute of the University of Pennsylvania. And about Bangor, near Skowhegan; this is probably where he landed. And he stresses the quietude of the area of Skowhegan, the break with the urban fast-pacedness. ‘It was so quiet, he said, much more quiet than I could bear.’ Quiet, yes, but that’s precisely it. In the studio where he lives, there is a refrigerator. Gary Hill even describes its contents: prepared meals, a bottle of white wine, a six-pack of Coke bottles, mineral water, cheese and even some desserts. And the noise this refrigerator makes fills the whole space, in an overbearing, obsessive manner. An agonizing struggle ensues: should the refrigerator be unplugged? Or not. Certainly, unplugging will bring about the certain return of tranquillity, in harmony with the natural setting of the place. It would even be an environmentally responsible gesture. By not unplugging it, he will obviously preserve its contents and the next day’s lunch. Unable to fall asleep, Gary Hill will finally decide to unplug the fridge: ‘I turned it off.’ Cheers from the audience.

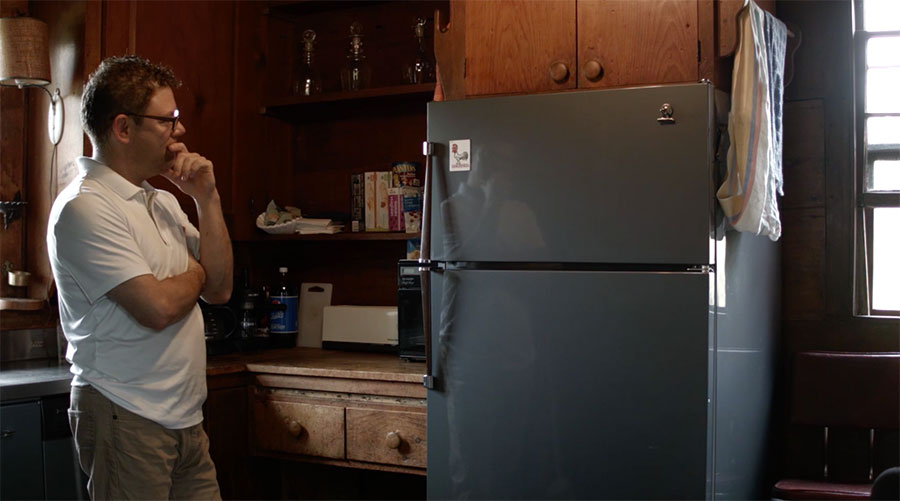

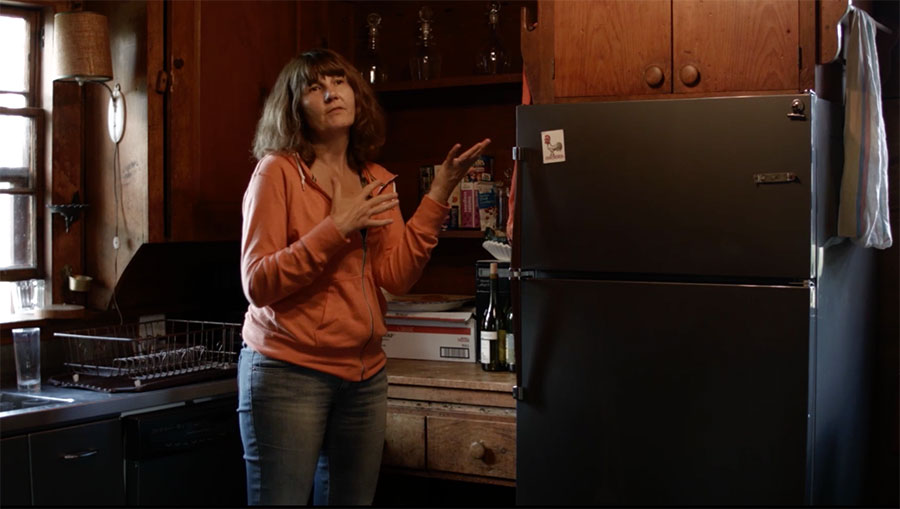

During a residency in Skowhegan in the summer of 2015, Charlotte Lagro discovered the sound archive of the conference as well as the kitchen of one of the oldest houses in the area, the Red Farm. Rustic and timeless, there sits, in-between window, dresser and sideboard, a hefty refrigerator. Incongruous in the setting, hieratic, polished, this modern and purring storeroom will quickly become the object of her attention, to the point of becoming the main focus of her artistic concerns. During the nine weeks of residency, she will invite the artists present, invited theorists and passing guest speakers to talk about it. And they, facing the camera, will join the game, scrutinizing the refrigerator from every angle. Its graphite grey, its mahogany handles with chrome fittings, its seventies look. Is it original, was it refurbished, customized, entrusted to a bodywork craftsman to be painted? Yes, its colour is industrial, but what type of spray gun did they use? And what kind of spray can, for the finishing details? Its ‘opalescence is boring,’ says one. ‘Its smell is peculiar’ remarks another. ‘All that wood is a little crazy, its colour is amazing, aubergine but with not too much purple, says Ryan Trecartin. Theaster Gates does not beat around the bush: ‘it’s a refrigerator that simply blows you away,’ he says, before making an inventory of its contents: wine, beer, olives, peaches and whipped cream. Michelle Grabner remarks upon its haptic qualities, the perception of this singular body in the environment: that which touches, that which is touched, the imprint of the place and the fingerprints, which are surprisingly not to be found on the streamlined and polished surface of the Red Farm fridge. No one mentions the history of art. Neither the avatars of the readymade nor the appropriation or recycling into art object of many a refrigerator. So much for Bertrand Lavier, Jean Tinguely, Jimmy Durham and Jean-Michel Basquiat. No, it is this particular refrigerator that interests them all. And Neil Goldberg wonders: ‘You’re interested in how the refrigerator exists in the lives of others, but to what extent does it interest you, you personally,’ he asks the artist. At a party organized between the residents, a costume party, Charlotte Lagro appears as a cardboard refrigerator. Her answer is clear: she is fully devoted to her fridge and definitely attracts interest. Hence Jonathan Berger’s enthusiasm: this refrigerator is exceptional, it is even better than any of the artworks he has seen in the past six months. And he concludes: ‘I have this sort of art-shaped hole in my heart, and it is only filled by this.’ ‘The art-shaped hole in my heart’, that will be the title of the film.

Artfully vacuous or, contrarily, brimming with visual and commercial imagery, the film is all the more singular because of its simple and direct comments about an object which is, after all, highly banal, and the fact that all this occurs in a place dedicated to research, where one would rather expect an overflow of theoretical discourse or the introduction of hyper-productive strategies. No, far removed from any parodial temptation, Charlotte Lagro transforms a refrigerator in a ‘conversation piece’. Throughout their considerations, the protagonists of the film – opening and closing the fridge – fill it or take things out of it. This refrigerator is not a work of art, but rather, it catalyses art, conceals it, provokes considerations on its design, its shape, its colour, its history, its usefulness, its environment. In fact, the situation is much less absurd than it seems.

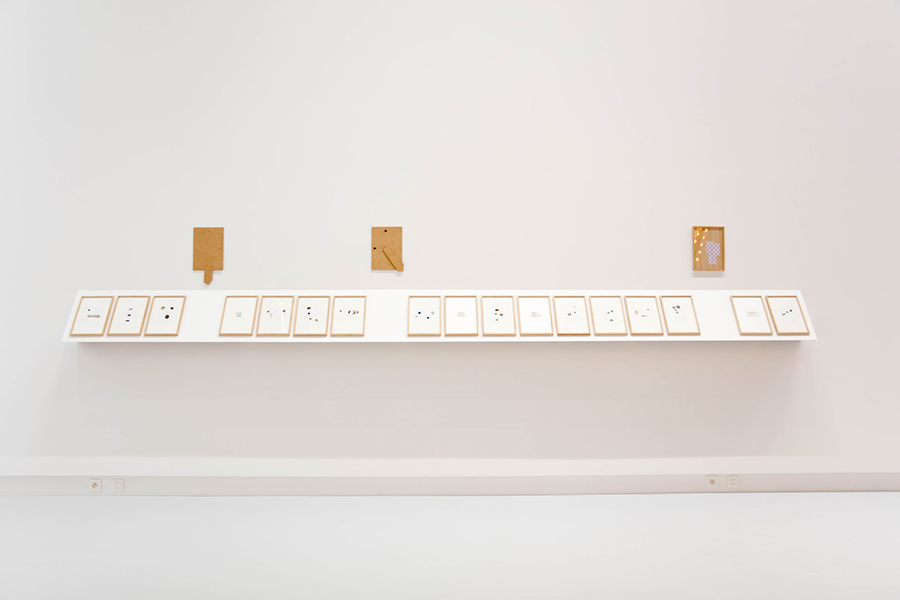

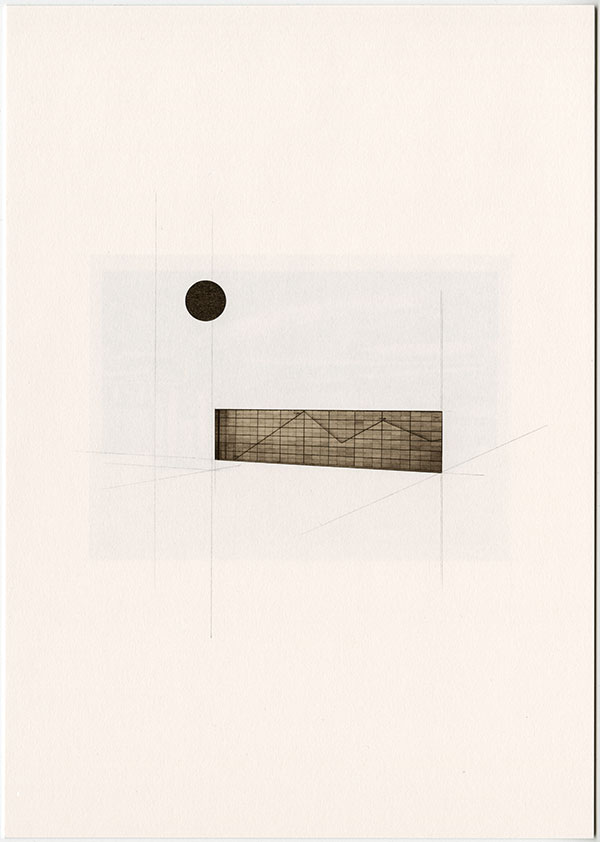

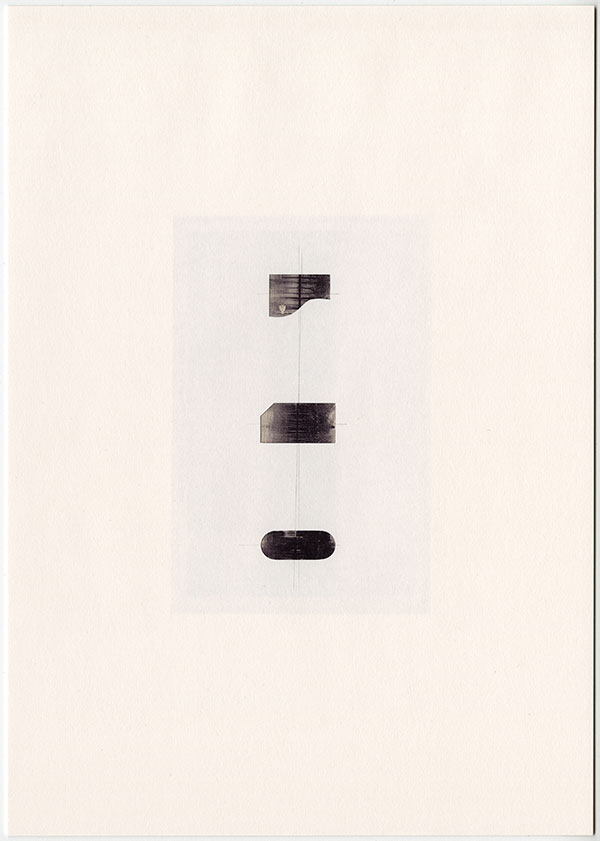

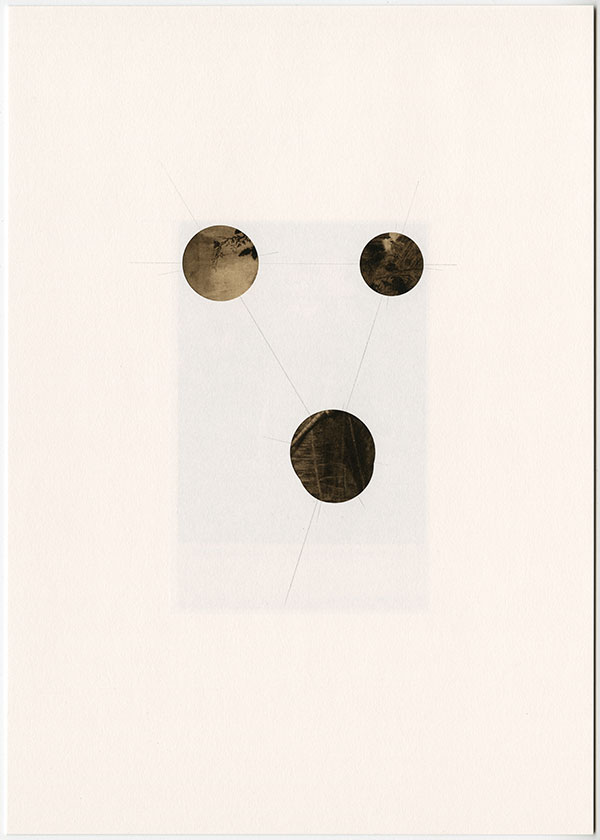

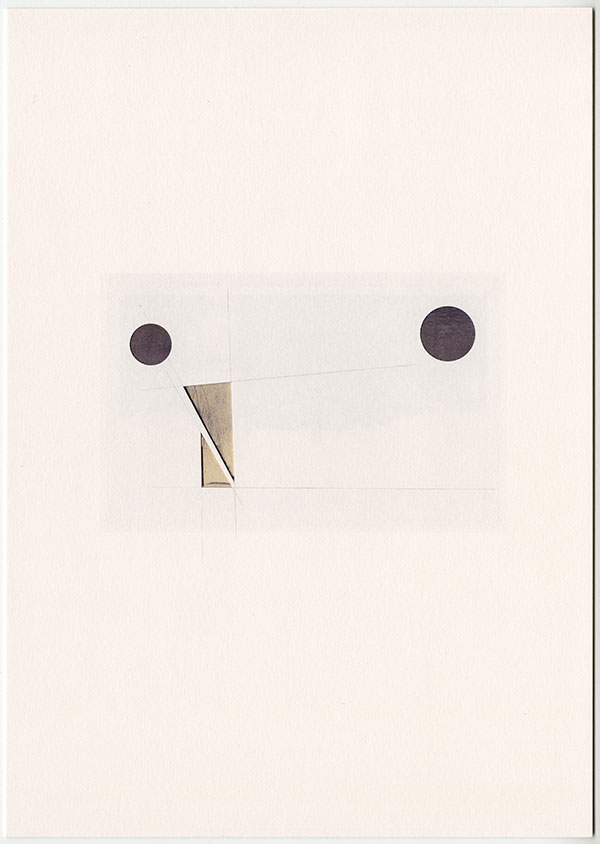

As such, the exhibition that results from it functions as a whole. As a counterpoint to the projection of the film, Charlotte Lagro highlights this sentence pronounced by Gary Hill in 1996: ‘And … it was quiet. Actually it was a lot more quiet than I could stand.’ The quote functions as a statement. Five large digital prints complete the set-up: a not-too-purple eggplant, a strange unicorn, a heart placed on the rack of a refrigerator, the bodywork of a car, an airplane in flight. It is an ancestor, with riveted fuselage, with rectangular windows framed by curtains, like those of a country house. Five images that refer to the reflections expressed by the protagonists in the film: this refrigerator is like a unicorn, hybridised through its refurbishment. ‘It was so, it was like a unicorn or something.’ It is eggplant colour. ‘it was like a little eggplanty but not with a lot of purple in it.’ Its body is like that of an airplane. ‘or maybe it’s like a plane’. Or like that of a car door, graphite grey. As for the heart, it is of course referring to the core of the whole work: ‘The art-shaped hole in my heart’. And one will perceive, discretely discernable in the exhibition space, the hum of the Skowhegan refrigerator, a purr that is like the heartbeat of the work.

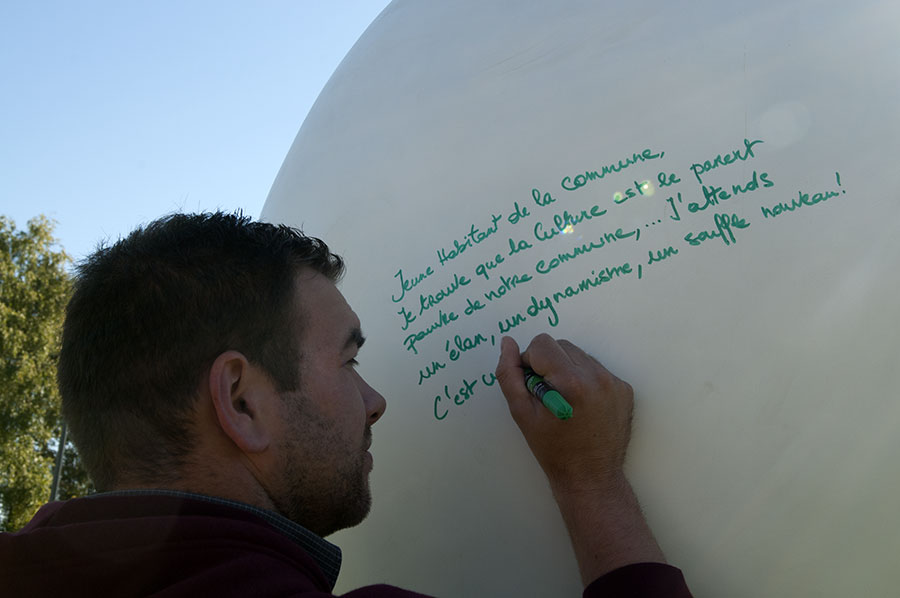

Born in 1989, Charlotte Lagro lives and works in Maastricht in the Netherlands. Videographer, photographer and visual artist, graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Maastricht in 2011, she was awarded the prize for Visual Arts Hermine van Bers 2015. She was recently a resident at the Résidences Ateliers Vivegnis International (RAVI) in Liège and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine in the United States. This exhibition is her first solo at the gallery.

Charlotte Lagro, The art-shaped hole in my heart, vidéo HD, son, couleurs, 2015, 00:11:39

[sociallinkz]