Invité à Bruges en 2008, c’est la contradiction entre tourisme et immigration, hospitalité, mobilité et centre fermé qu’Emilio López-Menchero pointera du doigt (Indonésie, 2008). Il y confronte deux imposantes sculpture, un nuage d’oreillers et une maison brugeoise aux pignons en escaliers, tous les signes extérieurs d’une confortable hospitalité hôtelière. La maison est pourtant un enclos grillagé et quatre porte-voix diffusent quatre voix de femmes aux accents chinois, indien, arménien et guinéen énumérant les nationalités recensées au centre fermé installé dans l’ancienne prison pour femmes de la ville, prévu initialement pour la détention d’étrangers(ères) en séjour illégal, puis également pour celle de demandeurs(euses) d’asile débouté(e)s. Quant au nuage de coussins, il est un hommage à la demandeuse d’asile nigériane Semira Adamou, tuée à Bruxelles National par étouffement lors d’une tentative d’expulsion. Le spectateur qui glissera son corps au cœur de ces oreillers de plumes y entendra Liza Minelli chanter le « Willkommen, Bienvenue, Welcome », du film « Cabaret » (1972), un refrain en boucle, une rengaine étouffée. M, le Géant (2007), ce Monsieur Moderne sans visage et à la silhouette neufertienne, ce monsieur anonyme et hypermoderne, qu’un jour Emilio López-Menchero introduisit dans une procession de géants historiques et folkloriques, est témoin de toute l’affaire. Il a même servi de cheval de Troie à l’artiste, afin de pénétrer dans l’ancienne prison de Bruges à la rencontre des illégaux et déboutés. Il est sous diverses formes omniprésent dans l’œuvre de l’artiste.

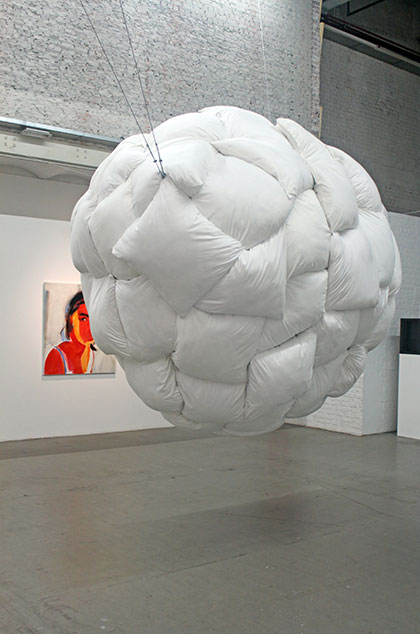

Invited to Bruges in 2008, in the work Indonésie (2008), Emilio López-Menchero points out the contradiction between tourism and immigration, hospitality, mobility and detention centre. Here, he juxtaposes two imposing sculptures: a cloud of pillows and a traditional Bruges house with gables in the shape of staircases, with all the external signs of comfortable hotel hospitality. However, the house is a wire cage and from four loudspeakers come the sound of four women’s voices speaking with Chinese, Indian, Armenian and Guinean accents, reading out the different nationalities identified in the detention centre inside the city’s former women’s prison, which was initially intended for detaining illegal immigrants, then later for failed asylum seekers as well. The cloud of pillows is a memorial to the Nigerian asylum seeker Semira Adamou, who was suffocated to death at Brussels Airport during an attempt to expel her from Belgium. Viewers who stand in the centre of these feather pillows hear Liza Minnelli singing ‘Willkommen, Bienvenue, Welcome’, from the film Cabaret (1972) – a refrain on a loop, a stifled rendition of the same old song. M, le Géant (2007), a modern man with no face and a Neufert-like body, an anonymous, hypermodern man that one day Emilio López-Menchero introduced into a procession of historic and folklore giants, witnessed the whole thing. The artist even used him as a Trojan horse to get inside the former Bruges prison to meet illegal immigrants and failed asylum seekers. He is omnipresent in various forms in the artist’s oeuvre.

Emilio López-Menchero

Brugse Huis (part of Indonesie !), 2008

Technique mixte et dispositif sonore

Emilio López-Menchero

Sacs (de la série Indonésie !), 2008

Encre de chine sur papier, 185 x 150 cm

Emilio López-Menchero

Manifestation (de la série Indonésie !), 2008

Encre de chine sur papier, 185 x 150 cm

Emilio López-Menchero

Molenbeek, (de la série Indonésie !), 2008

Encre de chine sur papier, 185 x 150 cm

Emilio López-Menchero

Willkommen, Bienvenue, Welcome (part of Indonesie !), 2008

Oreillers et dispositif sonore, dimensions variables

Emilio López-Menchero

Tricot (Indonésie !), 2008

Photographie couleurs marouflées sur aluminium, 150 x 185 cm

Edition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero

Trying to be Cindy, 2009

Photographie couleurs marouflée sur aluminium, 122 x 60 cm. Édition 5/5

Emilio López-Menchero ne pouvait que s’emparer du célèbre cliché que Man Ray fait de Marcel Duchamp déguisé en femme, cette photo d’identité travestie de Rrose Selavy, « bêcheuse et désappointante, altière égo » de l’artiste, « Ready Maid » ducham¬pienne. Habiter Rrose Selavy (2005) est l’archétype du genre, du transgenre. De même, il était en quelque sorte attendu, ou entendu, qu’il incarne également Cindy Sherman (2009). Depuis ses tout premiers travaux il y a plus de trente ans, l’artiste américaine se sert presque exclusivement de sa propre personne comme modèle et support de ses mises en scène. Regard sur l’identité, frénésie à reproduire son moi, son travail est ultime enjeu de déconstruction des genres entre mascarade, jeu théâtral et hybridation. De Cindy Sherman, Emilio López-Menchero a choisi l’un des « Centerfolds » réalisés en 1981, ces images horizontales, comme celles des doubles pages des magazines de mode et de charme, commanditées par Artforum mais qui ne seront jamais publiées, la rédaction de la célèbre revue d’art estimant qu’elles réaffirment trop de stéréotypes sexistes. L’artiste américaine — et du coup Emilio López-Menchero — incarne une femme vulnérable, fragile, sans échappatoire, captive du regard porté sur elle.

Emilio López-Menchero simply had to appropriate Man Ray’s famous photo of Marcel Duchamp dressed as a woman – the identity photo of Rrose Selavy, ‘stuck up and disappointing’, the artist’s ‘alter ego’, Duchamp’s ‘Ready Maid’. Trying to be Rrose Selavy (2005) is the archetype of the genre, in this case a change of gender. Similarly, it was in some way expected, or understood, that he would also incarnate Cindy Sherman (2009). Since her earliest works over 30 years ago, the American artist has almost exclusively used herself as her model and the basis for her compositions. Examining identity, a frenetic need to reproduce her ‘me’, her work represents the ultimate challenge of deconstructing genres, using farce, theatrics and hybridisation. Emilio López-Menchero chose one of Cindy Sherman’s Centerfolds from 1981. These horizontal images, like the double-page spreads in fashion and girly magazines, were commissioned by Artforum but never published, because the editor of the famous art journal believed they reaffirmed too many sexist stereotypes. The American artist – and therefore Emilio López-Menchero as well – is depicted as a vulnerable, fragile woman with no means of escape, held captive by the gaze of others.

[sociallinkz]