The beauty of the devil

(…) Jacques Charlier appeals to yet another mystic, and not one of the least important, Teresa of Avila, when he installs “Himmelsweg” (1987) in Pierreuse in Liège, in the Chapelle Saint-Roch in 1991. A passage written by Therese of Avila catches his attention: “All the books say about the agony and various tortures the demons subject upon the damned, all this is nothing compared to reality: there is between the one and the other the same difference as between an inanimate portrait and a living person, and to burn in this world is nothing in comparison to the fire in which we burn in the other.” “Himmelsweg”, the road to paradise, evokes the resurrection of the flesh, sin, hell, the genius of evil and his deceptive schemes, like the tunnel of death of the Nazi extermination camps. These give the ramp made of sticks and barbed wire that leads to the door of the gas chambers the name Himmelsweg.

Ah, the image of the Evil One can be so appealing! Jacques Charlier revives a major work of romantic sculpture, the two versions of “Triomphe de la Religion sur le Génie du Mal” (Triumph of Religion over the Genius of Evil), one by Joseph Geefs, the other by his brother Guillaume, the first kept in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, the other sitting at the foot of the ornate gothic pulpit of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Liège, in the very place where we should find … the first. Yes, but guess what: the fallen angel sculpted by Joseph Geefs was considered too sublime. “Joseph portrays a youthful dreamer who, with a broken sceptre, crown held in a weary hand, seduces by his ambiguous beauty, » writes Jacques Van Lennep to whom we owe a fascinating study on the subject. Apart from the wings of a bat, it is a man of great classic beauty, almost naked, a drape covering the groin; his form following a serpentine curve. He is young, smooth and graceful, almost androgynous. Even the snake at his feet seems to languish. The parishioners will not remain unmoved by this sculpture which looks more like Adonis than Lucifer, and which will apparently also inspire an unusual devotion and popular fervour. Faced with this much carnal intensity, the Fabrique d’église (Church Council) will commission a second version of the Genius of Evil, this time from Guillaume Geefs. The latter will represent the angel of darkness a little less bare, hips draped and covered, closer to the satanic iconography, horned so as to dehumanize him, at his feet the Apple of the Fall, consumed since marked with a bite. Chained and therefore more Promethean than his predecessor, his face contorted, Lucifer protects his head from divine punishment, which of course, is more consistent with the original order and reassures the clergy.

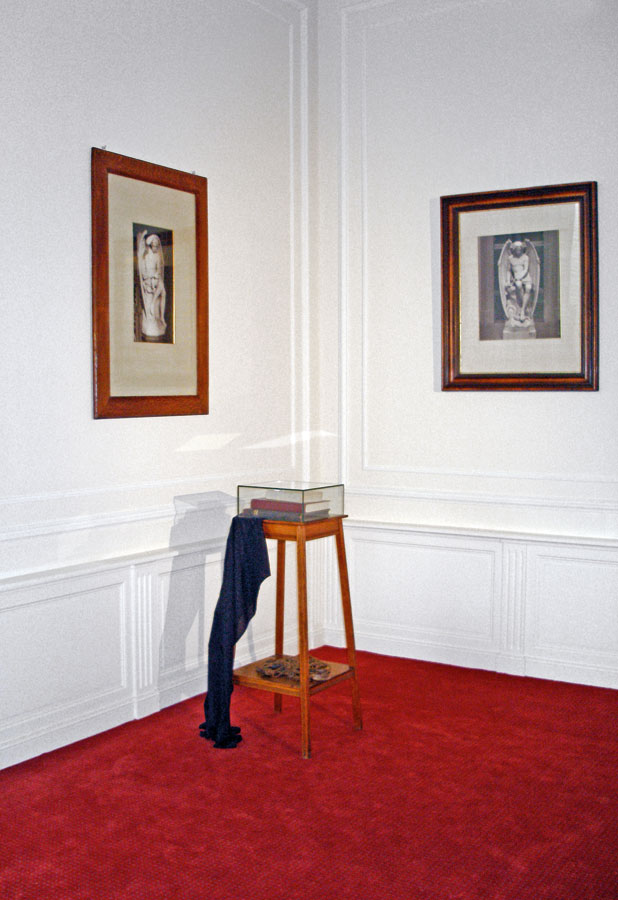

In Jacques Charlier’s installation, the framed photograph of the sculpture of William Geefs hangs above a small pedestal table draped in black. Chains are arranged on the bottom shelf. On the table, there are three books: a Carmelite study on Satan, an old science book on Air and the Memorial of Belgian Jews exterminated at Auschwitz. This is the reality of the genius of evil; and the greatest mistake would be to forget.

It is obviously not insignificant that Charlier would place a Carmelite study among the three books on the table. In fact, he creates this work while the controversy known as the Auschwitz Cross (1984-1993) fully rages – the installation of a congregation of Carmelites in the extermination camp, the starting point of a serious crisis that quickly transcended the religious conflict to embed itself within the very fabric of Polish and world history.

Appropriation of memory, instrumentalisation of images, “Auschwitz”, in the words of Annette Wieviorka, “has increasingly become disconnected from the history it produced”. Some realize that the saturation of memory threatens the very effectiveness of memory, and that it is difficult to know what it takes to desaturate memory by something other than forgetting. How then shall memory be reinvented, a working memory, a memory that is not a mere result, knowing that forgetting causes the eternally repeated fall. (…)

Le Merveilleux et la périphérie, Chapelle St-Roch, Liège 1991.

Himmelseg, chemins de paradis, Maastricht 2008

[sociallinkz]