The pretty faces of apostles

I think of Ludwig Feuerbach, disciple and critic of Hegel, of this passage which Guy Debord did not hesitate to highlight in his “Société du Spectacle” (Society of the Spectacle) in 1967: “No doubt our time prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, representation to reality, appearance to being, writes the philosopher. What is sacred to him, is only illusion, but what is profane, is the truth. Better still, sacredness grows in his eyes as truth decreases and illusion increases, so that the highest degree of illusion comes to be the highest degree of sacredness.” Sophie Langohr has perfectly perceived this dialectic, this dichotomy – and confusion – between illusion and sacredness, even to the point of profanation, I would say, in the full sense of the term: to make the holy and pious image even more profane than it is, to reduce this image, while sublimating it, into an image of desire and happiness than can only be desired without ever attaining it. This glorious body, the body of the Blessed, the resurrection of the flesh, would it be that of the Christian resurrection or of a rampant ageism, a starified ideal, an iconizing paradigm, arty, crowned with both the glory and mystery of creation and transfiguration?

The question arises in the context of the new series of images produced by Sophie Langohr. After having transfigured the muses of fashion in virgins and saints, here she reverses the process and revamps the Fathers of the Church! And this time, it is a homogeneous set of fourteen polychrome sculptures of the 17th century, the happy compromise between a late Gothic and a measured Baroque style, that the artist appropriates. Sophie Langohr uses all the artifices of professional shooting and studio work to transfer all the glory and fame of the models, celebrities and models of today to these saints carved by Jeremias Geisselbrunn in around 1640 for the church of the Miners in Cologne, now standing at the pillars of the church of Saint Nicolas in Eupen. Here are the icons of the Apostles, posing for this unexpected second (of) eternity. The casting is rather curious, to say the least.

Apart from the apostle John who is, of course, the youngest, all these apostles are bearded, wise and in the fullness of life. Sophie Langohr has, in this respect, fashion and trends to thank for: thanks to the hipsters, advertising today is full of bearded and hairy men. Shaggy hair is all the rage. The hipster is actually “trendy”, his look is stylishly neglected, he sports a dishevelled hairstyle; hirsuteness is actually essential, to the point where some get hair implanted at great expense. The hipster is an “early adopter” who buys quickly and turns away even faster, from the moment he finds that what he consumes has become too common. Hipsters are therefore well known to the marketers who sell them what they think they invent. This is a target which advertising presents as an icon of modernity. As a phenomenon of the new century, the hipster is about to be dethroned. The webzines and social networks announce – and orchestrate – the arrival of “Normcore” in the fashion world. The phenomenon, whose name derives from the contraction of the words normal and hard-core, is based on the “non-style”; the aim is to express specialness to the point of sameness. Be crazy, be normal, look like a teenager from the early 90s or, if you are fifty or more, like Steve Jobs himself. This will make the heyday of black turtlenecks and straight-legged and faded blue jeans .

But back to our bearded men of advertising which Sophie Langohr has tracked on the net. The issues are not the same as with the muses of New Faces. Here, there is no question of smoothing the image down to the pixel; everything has to do with the expression, an artificial natural air corrected under the lights of the shoot and during the postproduction of the images. The care of the self, to use the terms dear to Foucault, the ego business, the staging and eroticisation of the appearance, the self esteem, hedonism, tribal fusion, the rational and the passionate: the male icons of advertising must above all be charismatic. These are style icons. This time, Sophie Langohr, confronting the apostles with the icons of fashion, sought similarities, affinities in the traits and attitudes, and photographed the faces of statues as if they were stars and models. The shooting has since taken over the infographical treatment; the artist only gave the pretty faces of these apostles some basic facial care. From that point on, blur, grain and backlight are all that is needed. Advertising has since long understood: “the starting point is absolute blackness, wrote Gérard Blanchard already in 1968 in Les Cahiers de la Publicité about the eroticisation of advertising, because the myths are more or less laced with shreds of night. The artifices of photography, soft focus, lighting and backlight are all ways to give the image an ambiguous air of interpretation. The Amphitrite of advertising is born at night.” The recipe still works.

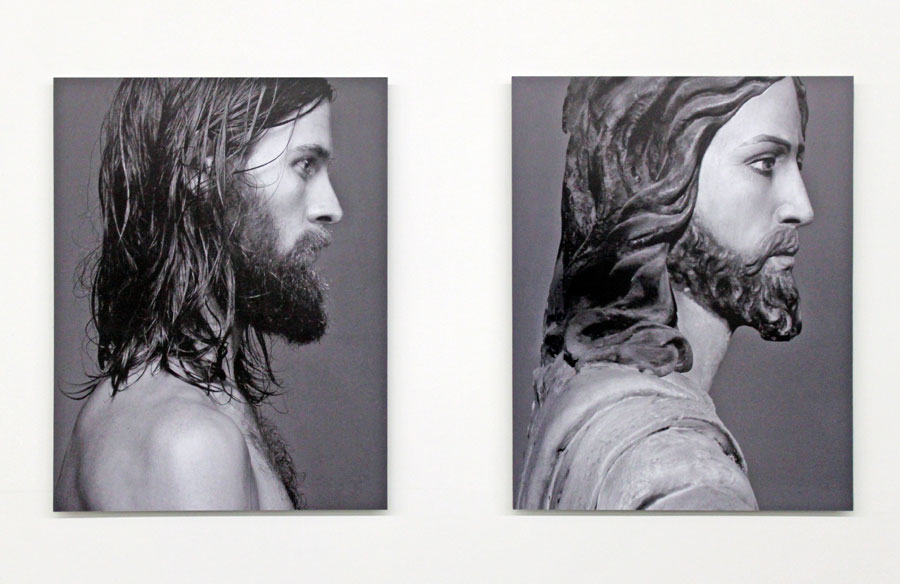

So here we have St. Peter, as the false fraternal twin of Philip Crangi, a New York jeweller who uses historical quotes, ancient artefacts, Japanese armour, baroque silverware in his urban, punkish and ethnic creations. St. Matthew, the dark introverted one, has only to get a tattoo of a living dead on the shoulder or a Christ-like face crowned with thorns on the arm to fully resemble the Greek model Dimitris Alexandrou. Largely forgotten despite his prestige in the early church, James the minor was the leader of the Church of Jerusalem and wrote one of the apocryphal gospels. In life, we need to be able to bounce back, revive ourselves, says Aiden Shaw, writer and composer turned model after scouring the gay porn studios in Los Angeles, a route that has enabled him to enact the figure of the old dandy whose experiences make for a great face. He apparently enjoys cult status and his latest music video is called « Immortal ». Martin Scorsese has directed St. Paul while shooting the short film for Blue Channel, a veritable turnip by the way. Simon the Zealot and Jeremy Irons will have to choose: all that is needed is a cosmetic surgery on a nasal appendage for the one to pass as the other. Lee Jeffries photographs the faces of the homeless in major cities: his features are a perfect match with those of Saint Andrew. Model Mariano Ontanon has the look of the Latin lover, even if he just grew his beard for Givenchy’s Fall/Winter 2013 campaign. And now he looks like Saint Bartholomew. Among these diptychs, there is one particular exception to the rule of the portrait: Sophie Langohr has appropriated a profile photograph of Thomas Medard, a young singer from Liège, photographed by Gilles Dewalque. From the front he looks like Saint Thomas, you have to see it to believe it.

Sophie Langohr profaner? Yes, in the sense that – without secularising them, quite the contrary – she desacralizes the faces of saints by placing them under the lights of the current media illusions. Yes, since she appropriates their use, abolishing all separations through a subjective photographic practice that is quite opposite to the usual documentary truth when it comes to photographing works of art. Sophie Langohr somehow takes the works of Jeremias Geisselbrunn out of the museum.

By confronting works of the past, distant auratics in the sense understood by Walter Benjamin, with immediate, virtual images, gleaned on the Internet, her works make us aware of the collapse of distance and the intense proximity within which we live. Undoubtedly, the works of art of the past are no longer seen by artists as a repertoire of subjects or models to imitate or rebel against; “they appear under the guise of an “already there”, a familiar environment whose components are just as real and current as any everyday object.” The artist, and this is good, experiences them as material, interacts with them, uses them as tools. Indeed, he rediscovers their use.

[sociallinkz]