Between fantasy and denial, 2012.

Video with sound 24 min 51. Birzeit, West Bank

À servir, 2013.

Digital print. 43 x 46 cm

FR

L’identité, l’accueil ou l’ostracisme, l’inscription dans une communauté, la mémoire, le déracinement, les flux migratoires, l’exil sont au coeur des préoccupations de Marie ZOLAMIAN. C’est là toute l’expérience de l’itinérance, du départ et du retour, de la temporalité vécue du voyage, de cette topographie où se mêlent l’extérieur et l’intime.

D’origine arménienne, née à Beyrouth en 1975, Marie ZOLAMIAN pratique ce cheminement, cette mise en intrigue entre territoires réels et fictionnels, choisissant les médias adéquats au rythme de ses pérégrinations.

D’un séjour à Birzeit, en Cisjordanie, Marie ZOLAMIAN ramène une photographie souvenir, une singulière carte postale, trois oliviers étêtes, déracinés, ceps noueux et torchères fossiles. Leur stérilité, âpre, rugueuse, inquiétante, contraste avec la pyramide de fruits d’un étal de marché voisin. Elle ramène aussi ce film, ce long plan fixe, minimaliste et contemplatif, réalisé dans l’atelier mis à sa disposition. Devant l’objectif, il y a une tasse en verre posée devant la fenêtre ; y miroite une myriade de pigments dorés en suspension dans l’eau. « A travers le scintillement des paillettes qui composent le fluide précieux, on peut observer le coucher du soleil sur Birzeit, écrit Colette DUBOIS, dans le livret qui accompagne ce voyage. Les variations de la lumière déclinent toutes les couleurs de l’or et donnent au reflet qui se prolonge sur le rebord de la fenêtre tantôt des accents aigus, comme un fragment de soleil acéré, tantôt l’apparence d’une simple trace qui cherche à se fondre dans la surface ».

Certes, il n’y avait pas plus simple pour suggérer, évoquer toute la problématique de l’eau en Palestine, les planifications mises en oeuvre par l’Administration civile israélienne, les enjeux vitaux, écologiques, économiques et politiques cruciaux que concentre ce bien précieux. L’eau est ici métaphore des relations entre les peuples, et bien plus encore. « La pièce réfère directement aux citernes d’eau qui se trouvent sur les toits de Cisjordanie, continue Colette DUBOIS. Ces cylindres noirs et massifs évoquent des éléments inquiétants : insectes géants, armes étranges ou explosifs… Figurer ces citernes comme une tasse de liqueur flamboyante dans laquelle le regard plonge avec une délectation certaine, y loger le crépuscule qui porte toujours en lui la promesse que demain sera un autre jour, tient tout autant du fantasme que de la volonté de renverser le cours des choses. »

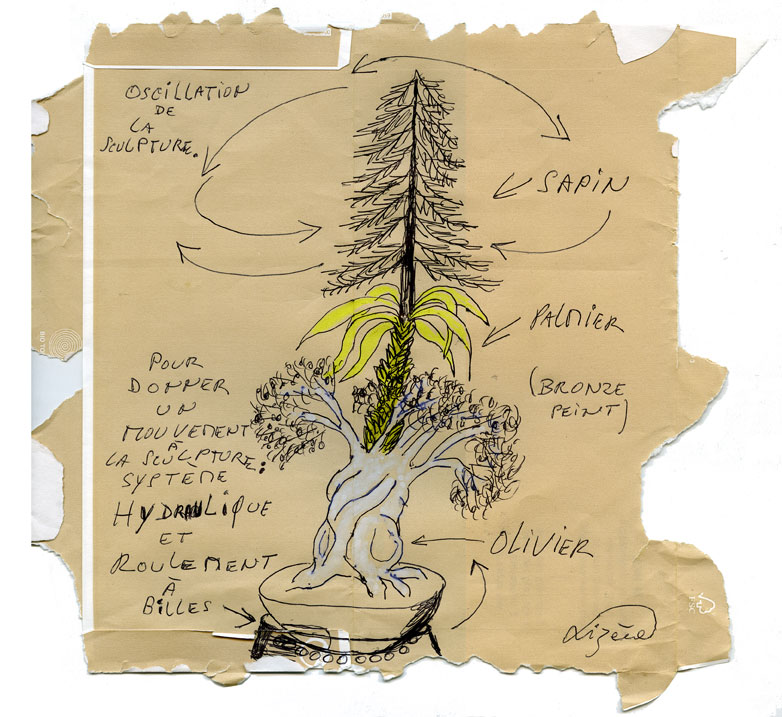

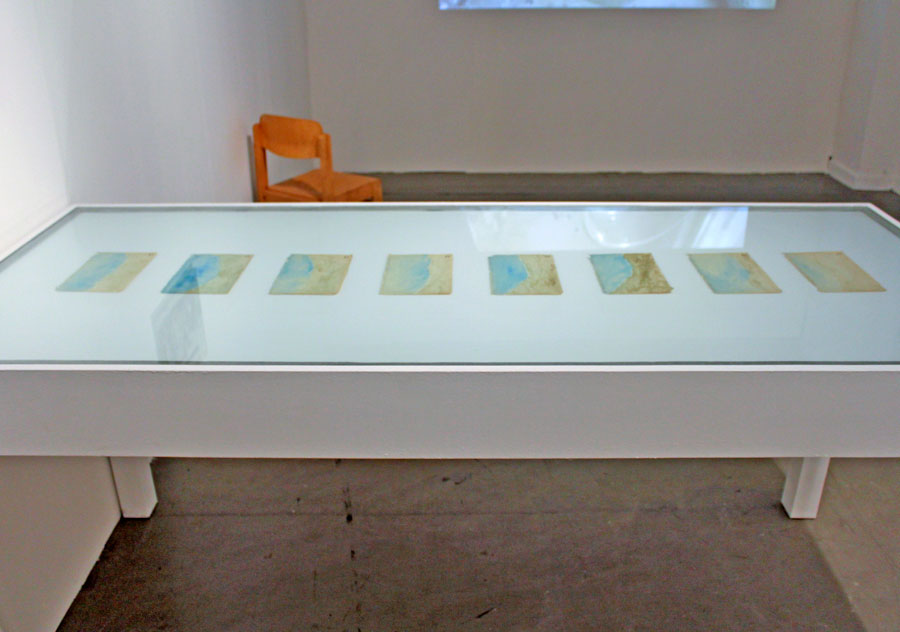

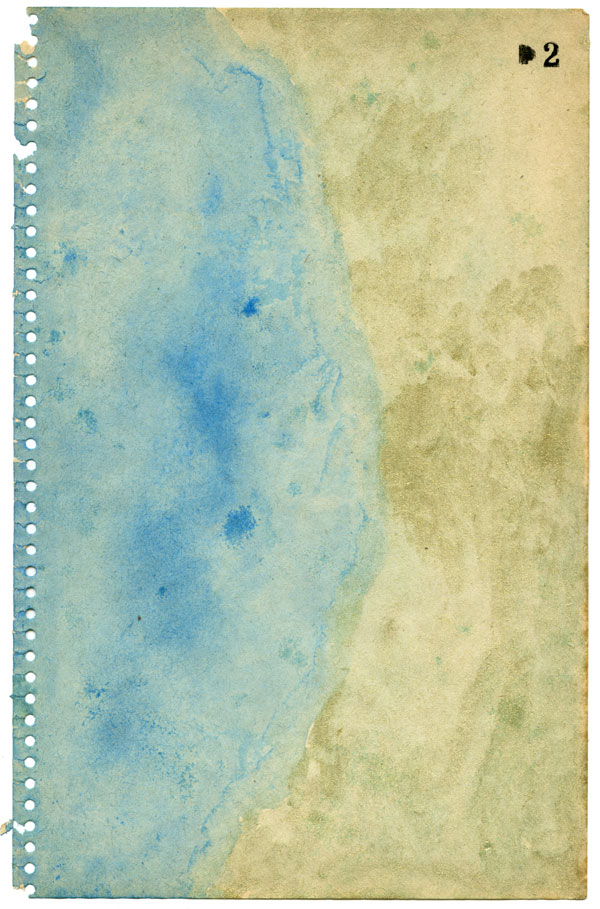

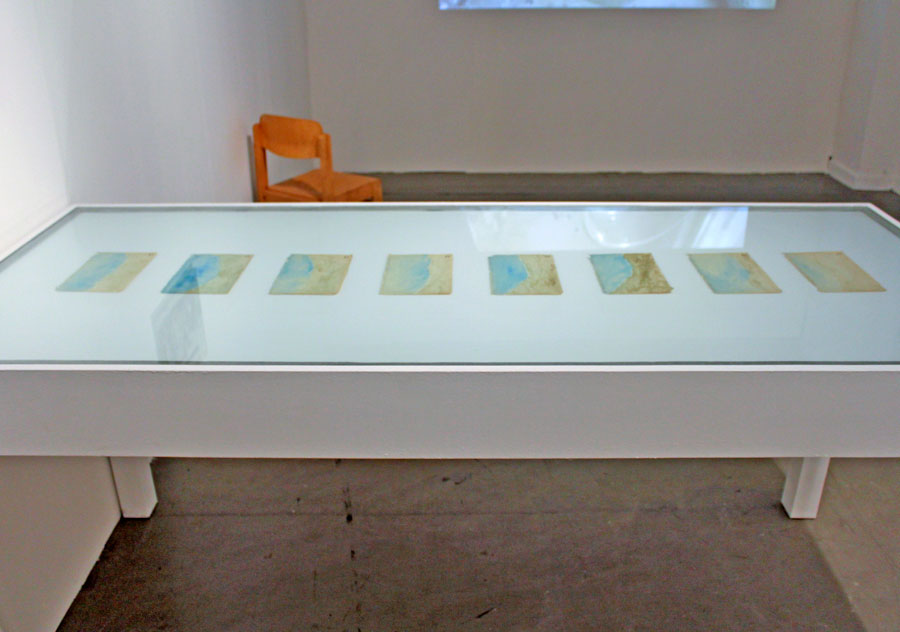

En contrepoint du film, une longue table est recouverte de dessins. Des planches, des tables, un atlas. Nous feuilletons l’oeuvre à loisir, laissant divaguer notre « volonté de savoir » ; nous arpentons cette cartographie, ces lignes en tous sens. Nous ne refermons l’atlas, le recueil de planches qu’après avoir cheminé un certain temps, erratiquement, sans intention précise, à travers son dédale, son trésor. Celui-ci est d’ocre et d’eau, nous cheminons sur des rivages d’or et, imaginons-le, sous un ciel aussi bleu que la mer. C’est là, pour reprendre les mots de Maria KODAMA à propos de l’Atlas de Borgès « un prétexte pour enraciner dans la trame du temps nos rêves faits de l’âme du monde ». Les dessins sont de gouache et d’eau, certains sur Caravelle Vélin supérieur. Tous se nomment « Mer morte ». Le sable est doré, l’or est liquide, c’est là le sel de la terre, cette alliance féconde.

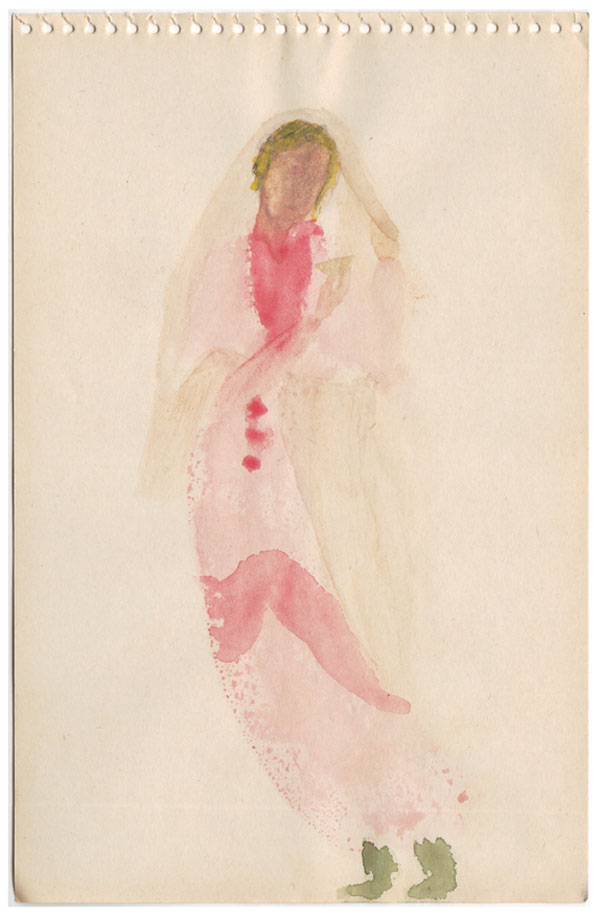

Dans sa pratique artistique, Marie ZOLAMIAN collecte, juxtapose, compose les éléments mémoriels, qu’ils soient proches ou lointains, singuliers et collectifs. Ainsi occupe-t-elle ce nouveau territoire d’expérience sensible, intime et inscrit dans le monde, enrichi de sens. Et comme dans un continuum, Marie ZOLAMIAN complète ici le dispositif mis en place d’une lente procession de femmes, esquisses sur papier inspirées de miniatures orientales et persanes. Elles sont prêtresses et servantes, évoquent à la fois le don, l’altérité, l’ivresse des sens et la soumission. Il fut question de l’huile et de l’eau ; toutes, cette fois, font l’éloge et l’offrande du vin, ce rituel séculaire, qui tout comme ceux qui concernent l’eau lustrale, se situe au carrefour des cultures et des civilisations. Je repense au poème mystique d’Ibn Al Fâridh, cet auteur du treizième siècle, à ces célèbres vers d’ « Al-Khamriya » : « Prends-le pur, ce vin, ou ne le mêle qu’à la salive du Bien-Aimé ; tout autre mélange serait coupable… ». Et devant l’or liquide de la tasse en verre de Birzeit, le coeur du poème mystique résonne singulièrement : « Notre verre, écrit Ibn AL FÂRIDH, était sa pleine lune, lui, il est un soleil ; un croissant le fait circuler. Que d’étoiles resplendissent au fond du verre quand on s’en abreuve ».

NL

Identiteit, gastvrijheid of uitwijzing, deel uitmaken van een gemeenschap, herinnering, ontworteling, migratiestromen, ballingschap: stuk voor stuk thema’s die Marie ZOLAMIAN – in 1975 geboren in Beiroet , maar van Armeense origine – na aan het hart liggen. Het leven als zwerftocht, als cyclus van vertrekken en terugkeren, reisbeleving als tijdelijk gegeven, als verruimende en tegelijk intieme ontdekkingstocht. Dat is de weg die ze bewandelt. Daarbij confronteert ze bestaande en fictieve werelden met elkaar, en kiest ze voortdurend de geschikte media om haar omzwervingen in beeld te brengen.

Aan een verblijf in Birzeit, op de westelijke Jordaanoever, houdt ze een bijzondere fotoherinnering over: een merkwaardige ansichtkaart met daarop drie geknotte, ontwortelde olijfbomen, knoestige wijnstokken en bomen als versteende fakkels. Hun dorre, ruwe, verontrustende levenloosheid staat in schril contrast met de frisse fruitpiramide op een marktkraampje vlakbij. Ze maakt er ook een minimalistische, contemplatieve film over in het atelier waar ze mag werken. Het wordt één lang statisch shot. Voor het raam staat een glazen kop gevuld met water waarin een oneindig aantal goudpigmenten schittert. “Door de fonkelende lovertjes waaruit het kostbare vocht bestaat, kun je de zonsondergang over Birzeit bewonderen,” schrijft Colette DUBOIS in haar reisverslag. “Het goud verandert telkens van kleur naargelang de lichtinval. De reflectie die op de vensterrand valt, krijgt af en toe scherpe accenten, als een splijtende zonnestraal, om dan weer te veranderen in een simpel spoor dat langzaam versmelt in de oppervlakte.”

Een eenvoudiger manier om heel de waterproblematiek in Palestina te schetsen, is moeilijk denkbaar. De planmatige aanpak van de Israëlische regering, de cruciale ecologische, economische en politieke belangen die hier op het spel staan: dat alles zit geconcentreerd in dit kostbare goed. Water is hier een metafoor voor de relaties tussen de volkeren en nog veel meer. “Het kunstwerk is een rechtstreekse verwijzing naar de watertanks op de daken van de huizen op de westelijke Jordaanoever,” vervolgt Colette DUBOIS. “Deze massieve zwarte cilinders verbeelden verontrustende elementen: reuzeninsecten, bizarre of explosieve wapens … De tanks zijn als mokken vol vlammende likeur, een schouwspel waar mensen met een zeker genoegen naar kijken. Tegelijk slorpen ze de schemering op die altijd de belofte in zich draagt dat er morgen weer een nieuwe dag komt. Deze voorstelling is niet alleen louter fantasie, maar draagt ook de wil tot radicale verandering in zich.”

Tegenover de film prijkt een lange tafel vol tekeningen. Planken, tafels, een atlas. We nemen rustig de tijd om het werk te doorbladeren en geven onze ‘drang naar kennis’ de vrije loop. Het is als een kaart vol kronkelende lijnen die we één voor één proberen te ontcijferen. We doen de atlas pas weer dicht na er een tijdlang doelloos in te hebben rondgezworven en rondgedoold, als in een labyrint vol schatten van oker en water. We wandelen langs gouden oevers en verbeelden ons een zeeblauwe hemel. Om Maria KODAMA te citeren als ze het heeft over “Atlas” van Borges: “Het is een voorwendsel om onze dromen over de ziel van de wereld te verankeren in de tijd.” De tekeningen zijn gemaakt met waterverf, sommige op Caravelle-velijn van topkwaliteit. Ze dragen allemaal dezelfde naam: “Mer morte” (“Dode Zee”). Het zand is goudkleurig, het goud vloeibaar, het zout van de aarde is symbool van vruchtbaarheid.

Geheugen en herinnering: het zijn elementen die Marie ZOLAMIAN voortdurend verwerkt, verzamelt en naast elkaar plaatst. Ongeacht of ze dichtbij of veraf zijn, enkelvoudig of meervoudig. Op die manier geeft ze vorm aan een nieuwe, (zin)rijke wereld vol gevoelige, intieme ervaringen. Als in een continuüm schetst ze hier een langzame stoet vrouwen. Schetsen op papier, geïnspireerd op oosterse en Perzische miniaturen. Het zijn priesteressen en dienstmeisjes die tegelijk symbool staan voor de gift, voor anders-zijn, dronken zintuigen en onderwerping. Allemaal zingen ze de lof van de wijn, die ze offeren als eeuwenoud reinigingsritueel, waarbij ook water en olie een rol vervullen. Een ritueel op het kruispunt van culturen en beschavingen. Ik denk hier terug aan het mystieke gedicht van Ibn AL FÂRIDH, een schrijver uit de 13e eeuw, en aan de beroemde verzen uit de “Al-Khamriya”: “Drink deze wijn zuiver of vermeng hem alleen met het speeksel van de Geliefde Profeet. Elk ander mengsel zou heiligschennis zijn …” Voor het vloeibare goud in de glazen kop van Birzeit weerklinkt op een unieke manier het hart van het mystieke gedicht: “Ons glas was zijn volle maan, hij is een zon die dankzij een halvemaan blijft draaien,” zo schrijft Ibn AL FÂRIDH. “Wie zich laaft aan deze drank, doet sterren fonkelen in het glas.”

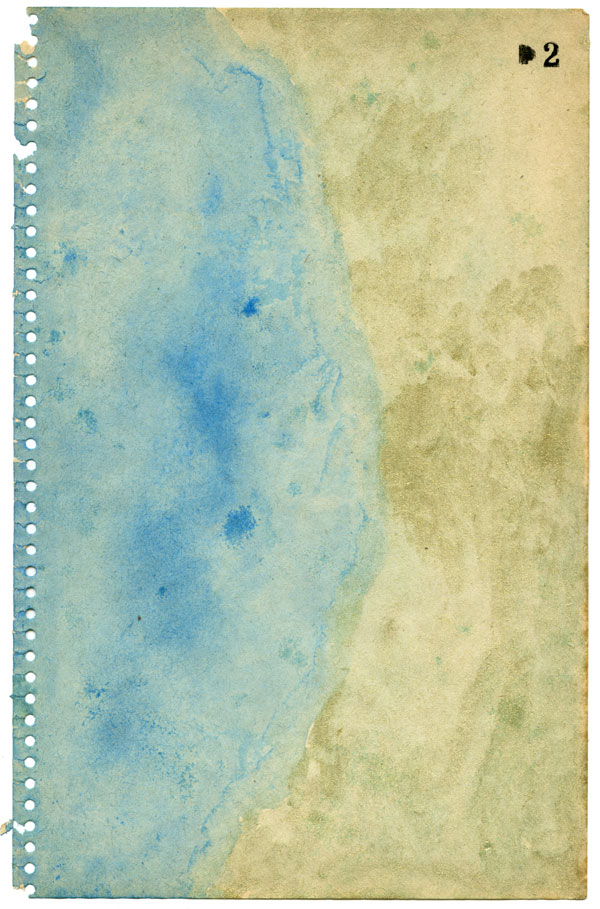

Mer morte, 2013.

Gouache on superior velin paper (8). 21 x 13.5 cm.

EN

Identity, acceptance and ostracism, community affiliation, memory, uprooting, migration and exile are a key feature of Marie ZOLAMIAN’s work. This is the migratory experience, the departure and the return, the temporality of the journey, this topography where the foreign and the familiar combine.

Of Armenian origin, born in Beirut in 1975, Marie ZOLAMIAN works with this process of creating connections between real and fictional territories, choosing her media to suit the tempo of her peregrinations.

Returning from a visit to Birzeit in the West Bank, Marie ZOLAMIAN brought back a souvenir photo, a singular postcard of three olive trees, lopped, uprooted, tendrils knotted, trunks fossilised. Their sterility, harsh, rough and disconcerting, contrasts with the pyramid of fruit on a nearby market stall. She also brought back this film, a long still shot, minimalist and contemplative, produced in the studio provided for her use. Before the lens stands a glass in front of a window; reflected in it are a myriad of gold-flecked pigments suspended in the water. “Through the sparkling flecks of the precious liquid, we can watch the sunset over Birzeit,” writes Colette DUBOIS, in the journey guide. “The changing light proffers every shade of gold and gives the reflection that lingers on the windowsill not only acute accents, like a slicing fragment of sun, but also the appearance of a mere trace that seeks to melt into the surface.”

There was no simpler way to touch on or convey the problem of water in Palestine, the plans implemented by the Israeli Civil Administration, and the vital, ecological, economic and highly political issues surrounding this precious resource. Here, water is a metaphor for relations between peoples, and more. “The work makes direct reference to the water tanks on West Bank rooftops,” continues Colette DUBOIS. “These huge black cylinders conjure up disconcerting images: giant insects, or strange, explosive weapons. Depicting these tanks as a cup of flaming liquor in which the viewer becomes delectably immersed, placing inside it the sunset which always brings with it the promise that tomorrow will be another day, has as much to do with fantasy as the desire to turn the tide.”

In contrast to the film, we find a long table covered in drawings: plates, tables, an atlas. We can browse the work at leisure, letting our ‘will to know’ ramble; we survey the mapping, the lines, from every angle. We only close the atlas, the collection of plates, after having wandered a while, erratically, without any particular direction, through its maze, its treasure. A work in ochre and water, we wander along golden shores and picture it under a sky as blue as the sea. It is, as Maria KODAMA described Borges’ Atlas, “a pretext to firmly root in the web of time our dreams made from the soul of the world.” The drawings are in gouache and water, some on high-quality Caravelle vellum. They are all called ‘Mer morte’ (Dead Sea). The sand is golden, gold is liquid; therein lies the salt of the earth, that fertile alliance.

In her artistic practice, Marie ZOLAMIAN collects, juxtaposes and composes pieces of memory, whether distant or recent, singular or collective. In doing so, she occupies this new area of experience that is sensitive, personal and a part of the world, enriched with meaning. As in a continuum, Marie ZOLAMIAN completes the process with a slow procession of women: sketches on paper inspired by oriental and Persian miniatures. They are priestesses and servants, conveying giving, otherness, the drunkenness of the senses, and submission. These are oil and water and all, this time, bring an offering of praise and wine, a secular ritual that, just like those involving the lustral water, sits at the crossroads of cultures and civilisations. I am reminded of the mystical poem by the 13th century author, Ibn AL FÂRIDH, and his famous ‘Al-Khamriya’: “So take it straight, though if you must, then mix it, but your turning away from the beloved’s mouth is wrong.” Likewise, watching the liquid gold of the Birzeit glass, the heart of the mystical poem has particular resonance: “Our glass,” writes Ibn AL FÂRIDH, “was its full moon, the wine a sun circled by a crescent. When it is mixed, how many stars appear!” (Translation from Th. Emil Homerin UmarIbn al-Fârid, Paulist Press, NY, 2001).

À servir, 2013.

Digital print. 43 x 52 cm

[sociallinkz]