The city that doesn’t exist

If you search for “Desert Cities” on the World Wide Web, the first hits are American cities in California and then real estate offers in Hurghada/Egypt. A medium-sized apartment is going cheap at €24,000. If you then go on to search for “real estate in Egypt”, you find such cities as “6th of October” or “Mirage City” with their embedded controlled settlements that offer everything from grocery deliveries to “religious service” all inclusive.

The government programme that gave rise to the Desert Cities around Cairo and Alexandria goes back to Anwar el Sadat. Back in the seventies, his plan was to catapult his country straight into the twenty-first century. As so often in the history of modern urban development, the aim was to build planned cities to do well what was of such political and social complexity as to appear insoluble.

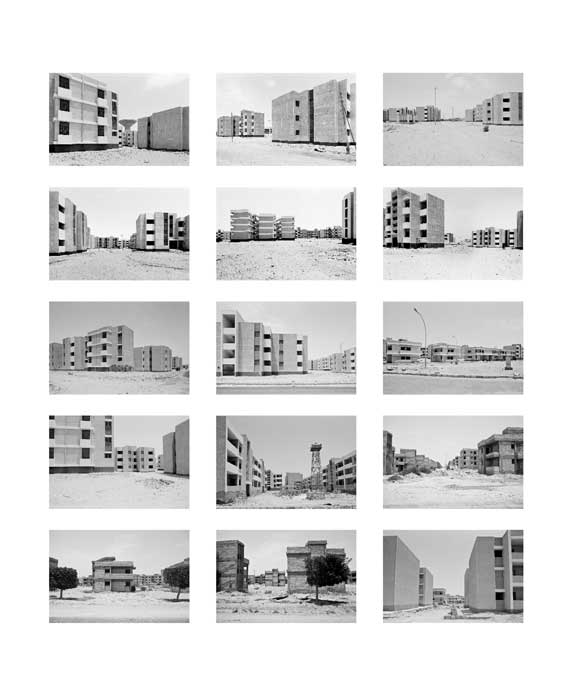

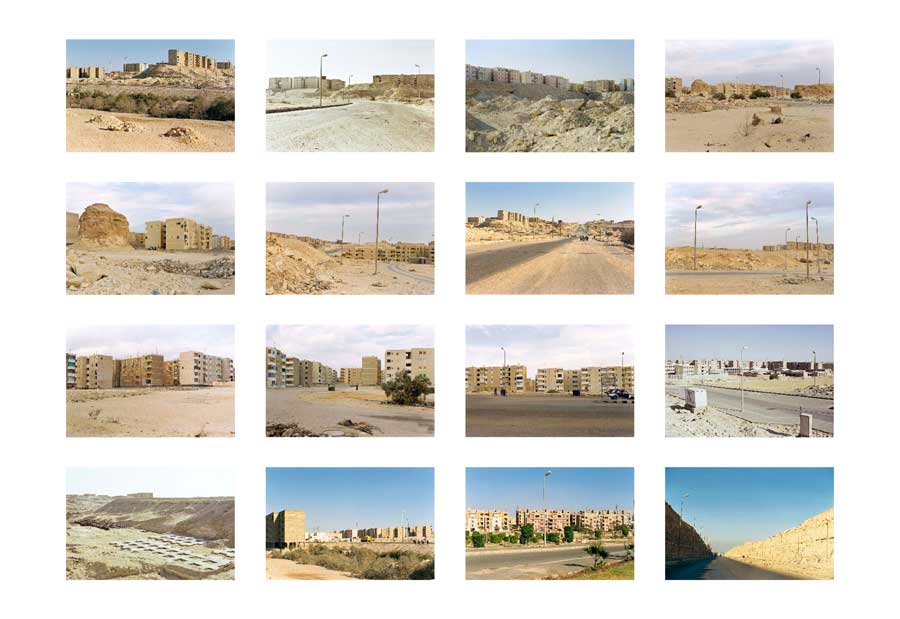

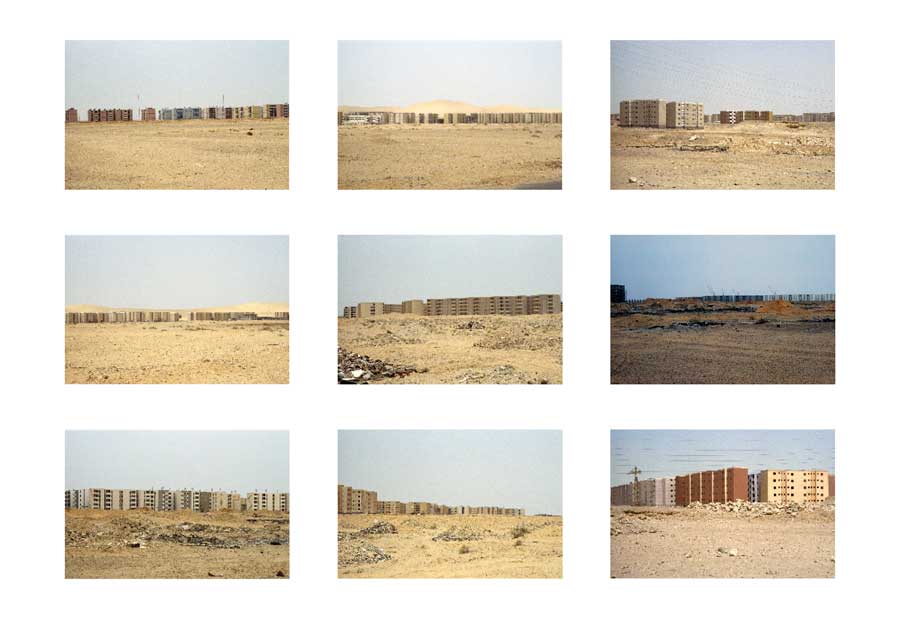

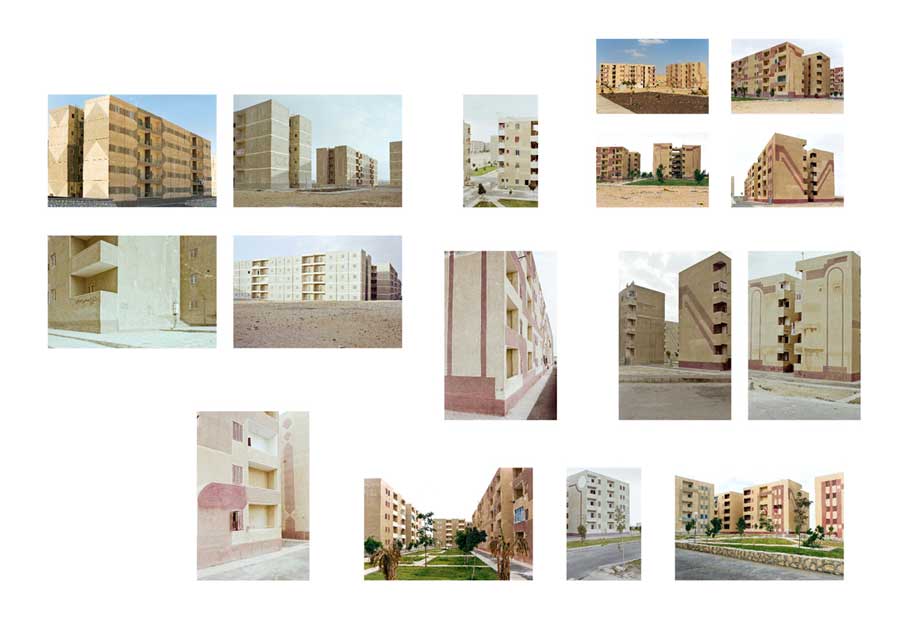

At first, cursory glance at Aglaia Konrad’s photoseries of these areas you cannot pinpoint the places to begin with: Asia, Africa, desert? Konrad focuses a direct gaze on these cities and their buildings. This is not architectural photography, nor documentary photography. Her way of seeing things is unadorned and draws our attention straight to the incidental nature of the history of the real setting. She shows that very poetry of the everyday image that cannot be captured but that rather lingers as an afterimage in fragmentary memory.

The photographs spotlight the key issue of “modernist architectures” as the spaces in between architectural development. Within individual photos, and all the more when they are lined up together, we can suddenly leap, as it were, from the sixties into the nineties and beyond. Reminded of Tati’s “Play Time” and the ridiculousness of modernised man, this gaze suddenly turns into concrete reality. It’s everywhere. The multifaceted nature of the pictures, the termite hill-like aspect of the agglomerations puts the photographs in the realm of scientific observation and landscape photography. Like picturesque, albeit mechanically recurrent rock formations, mountain ranges. Konrad’s view of this world is analytically detached, but never uninvolved. It is not the aesthetic and structural phenomena alone that fascinate the photographer but the absurdity of human activity and its potentialities expressed by the empty punctuated façades. Who – in the name of God – had to go and build these houses here – and why? The anthropological aspect of this viewing and looking creates more empathy through emptiness than through fate. How did they conceive the ideal person, the ideal family, who were to live there?

A conurbation such as Cairo – with currently more than fifteen million inhabitants – is one of the mega-cities of the modern world. Wedged in geographical confinement between desert, pyramids and archaeological sites, and the Nile Delta, the expansion and development of the city is naturally limited, as it were. In the nineteen-seventies, spinning off satellite towns seemed to offer the ideal solution to this fatal predicament. Similar to, albeit on a much larger scale than the real suburbs of Central European modernism in Frankfurt-Preungesheim or Berlin-Siemensstadt, for example, and following in the vein of Le Corbusier’s visions of a Ville Radieuse, the spin-offs around Cairo were pure dormitory towns linked to the heart city by big motorways and designed for some 500,000 inhabitants. Often, not even ten per cent of these potential populations materialised. In some places they are building again today. The aim is no longer to attract the working masses, the simple middle classes, but rather the high earners and the increasingly well-to-do. The result is clearly demarcated communities, irrigated and amenitised at inordinate expense, in whose swimming pools no-one would ever bathe publicly. The perfect illusion of a globally present quasi-movieland has become reality.

The surrounding desert and the view from afar, subdued, go to augment the disconcerting impression. These characteristics of the gaze preserve the condition, conserve and archaeologise in advance. You can feel the dry heat in the photos, that reflect on stones and structures. Continuing to look only increases the impression of dreariness. The sun really begins to burn. It blazes and makes the doorways and windows appear even blacker. The face of the landscape assumes remorseless features. Roads to nowhere. Lights with no function. Balconies never occupied. Faults in the water installation systems. Unfinished roads. Few cars. Rocks. Stones. Necropolis.

Reality and timelessness collide in a clash of times and spaces. Where has social space gone? Gingerbread style, Neo-Roman, in recent building projects. Tastes converge and, like the modern movement, are international. One image follows another. Rows upon rows of interrelated, overlapping aspects of local existence. The cityscapes are abstract structures, plausible on paper and from a distance, aesthetic, anti-social – and thus bringing about the opposite of what they were founded to achieve – in their form. Aglaia Konrad’s cinematic gaze turns the observers into external experts, strangers in and of themselves. The pausing, searching movement cannot be detached from the photographs but is rather ingrained in them. Associatively, memory searches for starting points, finding them perhaps in Antonioni, remembering ruined Western towns, the empty houses of Walker Evans, the empty roads of Eugène Atget’s early-morning Paris, and Dan Graham’s row houses from the late sixties. The views of modernity that Aglaia Konrad presents cut to the core, for their formal beauty in detail is lost in the desert in mass. Their ideals founder in view of the rapidly growing population. The once new architecture for the once new people of our grandparents’ generation at the start of the twentieth century is now nothing but a ruin to behold. The attempt to change people through architecture has failed. Coming to a halt in a modern building does not suddenly make you modern. The post-modern phase of new capital-driven pseudo-individualism has well and truly begun here, too, in the form of the demarcated new districts. The suggestion of luxury stands for prosperity and progress.

The represented cultures of the landscape are made up of misunderstandings, exploitation, false pity, the attempt to organise masses, and the false premise that they exist and may be organised as such, idealism, misguided ambition, corruption. These global phenomena join together in Konrad’s photoseries to form one side of the coin. There unfolds before our eyes a never-ending urban agglomeration encircling the globe like a ribbon. The anonymity of the places is symptomatic. Their identity, the modern will to structural change. The Desert Cities are just one part of these world cities. Four, nine or sixteen hours away by air. A Smithsonian sense of entropy sets in. Konrad gives a tour to the monuments of modernity. Periphery is everywhere and nowhere. The veil of exoticism and orientalism has long since been torn away. The transfigured view now only exists in anonymous image production for marketing apartments and villas. Barely good enough for selling travel adventures. Although as soon as we look at the pictures in the magazines we are sure that it doesn’t look like that there anyway. But these other pictures, that Konrad does not photograph but refutes, are like a prejudice in the back of our minds, something that we are willing to believe although we know full well that all the facts say otherwise.

Logical in itself is the dissection of modernity that Konrad performs by means of the photographic apparatus. The little image machine is, in and of itself, a representative of modernity. Without photography, media image production, modern existence would be inconceivable, too. Bauhaus would be less without the Bauhaus photographs of Lucia Moholy. Architectural modernism, but also the modern feeling of life, is intimately linked to photography. Only by means of their photographic presence in the media could buildings that were in many cases geographically far-spread create the impression of an international movement, e.g. in the legendary International Style exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1932. Buildings and landscapes, but equally political events, are immovables, firmly attached to specific places. Photography, film and video not only bear witness to their existence but also make them available for further processing, as it were. The heroic view of the first half of the twentieth century has worn thin, for one reason because spectacular achievements have become miniaturised, for example in the form of genetic research. Only building projects still have that trait of spectacular monumentalism because they are protuberances of individuals’ sense of mission and power.

Realism, in this context, is a category that holds a difficult position in contemporary art, but whose analytical eye is of great importance. The term abstract realism could be one category of description, one semantic field, one attitude that might be applied to Konrad’s gaze in view of its inherent contradictoriness. It is not just that we see what we see. It is not about the relationship between mass and individual. The viewer, looking down on a raving rock concert audience from far on high or on glittering Los Angeles, is not what interests Aglaia Konrad. It is not a landscape whose production of grandeur is relevant in its modern flavour. Rather, the persistent sound of rigid concrete, that has a sculptural quality but that also points out presences, inclusions and exclusions and, in connection with the desert sand, is possessed of a strange formedness, as if a giant had been playing with building blocks. Her landscapes are of a peculiar homelessness, the abstract compositions of space of immense beauty. The underlying political complex is constantly subcutaneously present. What to do?

Aglaia Konrad

Desert Cities, 2007-2009

digital print on acid-free cardboard, 110 x 80 cm