WORKS

EXPOSITIONS

BIOGRAPHIE

L'ESPRIT DU MAL, THE SWAN OF THE DEVIL, AGAIN

Many images have a fascinating persistence. This is true also of Leda and the Swan, which, since the Renaissance, has inspired many artists, including very major ones. To site just a few, in no particular order: Rubens, Correggio, Leonardo da Vinci, Gustave Moreau, François Boucher, Veronese, Michelangelo, Pontormo, Géricault, Poussin, Tintoretto, Cézanne, Otto Dix, Man Ray, Marcel Mariën, Cy Twombly, Salvador Dali, Francesca Woodman, or the actionist Otto Muehl. It is true that the myth of Zeus, transformed into a swan to seduce Leda, a sombre matter of vengeance among the gods of Olympus, is inspiring: it makes possible the presentation of an intimate affair, without showing it, while showing it. It gives artists an opportunity to express feminine joy and pleasure, which, in the case of Leda, is associated with an animal sensuality: sinuous, erectile, prehensile, a coupling with the divine, which, we must admit, is infinitely more rewarding than with the first chap that comes along, even if he is king of Sparta. Jacques Charlier, not without humour, will in turn decide to adopt both the myth and Leda into his work. Because of the complexity of the images and interpretations that her divine and extramarital adventure has generated, she is as attractive as Jeanne or Rita. There is, however, one difference: Leda belongs entirely to the realm of legend, the myths of origins.

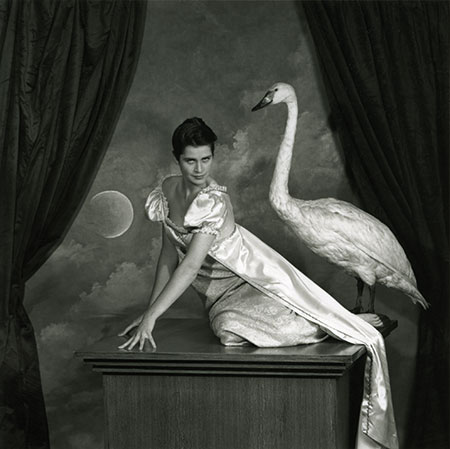

Red curtain and stormy sky on a night of full moon, the art here becomes the great theatre of illusions, simulacrum and tableau vivant for a burlesque theatre or carnival. The beautiful Leda, in her Empire style dress, poses next to a stuffed Zeus and seems to throw a discreet yet knowing glance at the spectator. Jacques Charlier does not turn the image into pastiche, he does not alter it, he inhabits it and haunts it. And the swan does not move a feather. The title, “L’esprit du Mal” (The Spirit of Evil) is intriguing. Certainly, revenge, deceit, the adulterous and unnatural union are the stuff myths are made of. Moreover, this union will produce an offspring in which will rage the war of opposites, love and hate. The metamorphosis of the god itself enlarges, doubles or multiplies to infinity the demonic potential of otherness. And, as we know, evil fascinates. In an interview with Stefaan Decostere, Jacques Charlier states that Leda is also among the favourite pictorial themes of Adolph Hitler. “He certainly took himself for Zeus fertilizing Germany,” he says. A version of Leda was indeed included in the great German Art Exhibition held in Munich in 1939. Its author is Paul Mathias Padua (1903-1981), an artist very close to the regime, author, among others, of two well known National Socialist propaganda works: “Der Führer Spricht” and “Der 10 May 1940”.

His “Leda mit dem Schwan” creates a scandal during the inauguration of the GDK in 1939. The painting, depicting a swan with a disproportionate neck fornicating a swooning Leda, is very sexually explicit, even violent. It will be held in the exhibition at the express request of Hitler and be acquired by one of his entourage, Martin Bormann , Nazi dignitary, counsellor of the Führer, one of the most powerful men of the Third Reich. In the aforementioned interview, Jacques Charlier opens the debate beyond the myth of Leda, and continues: “Nazism is primarily an aesthetic, that is too often forgotten. It is this aesthetic of absolute dramatization of life. The aesthetic excess preceded the murderous excess.”

Once their embrace is broken, the swan disappears, leaving Leda with two eggs from which Helen and Pollux, Castor and Clytemnestra will hatch. The versions of the myth differ with regard to the correct order of the occupants of these eggs. Suffice it to remember, however, that each egg holds a set of twins. Twins have always intrigued Jacques Charlier. Remember the angel and his double, which he drew for "Total's Underground" at the end of the 60s? “Total's energetic”, these angels are replicas of one another in the monozygotic universe which can only reflect itself and which revels, like Narcissus, in the image of its double. From Leda to the twins of the “Doublure du Monde” (The double of the World), from St. Rita to Melusina or Morgana, art here is a disillusioned physical reflection, a sign that the past could take over the present, an anguish born of a feeling of melancholy. In these works we have discussed, Jacques Charlier deliberately uses anachronistic time frames. His images are often a montage of heterogeneous times. He has perceived that the basic notions of the history of art such as “style” or “time” have a dangerous plasticity. In fact, they are never ever in a fixed place; they mark time differentials in motion. This is where they find their critical point. With Jacques Charlier, this kind of time crisis is often a reflection of a time in crisis. (JMB)

Jacques Charlier

L'Esprit du Mal, photographie N.B marouflée sur aluminium, 110 x 110 cm

(photographie : Laurence Charlier)

----> Lire en français